By Zhou Duo

Editor’s note: this is part two of a series of articles by a participant, albeit one who thought the students were too radical, in the 1989 people’s movement.

Part one is at https://www.yibao.net/2024/04/29/the-things-i-saw-in-may-and-june-1989-1/

Completely contrary to official statements, the May 4th demonstration was actually just about the largest of all of those held in the lead up to June 4th. The traffic throughout Beijing’s metropolis was almost completely blocked. By the time I arrived at the agreed-upon meeting point — in front of the Xinhua News Agency — no one in our party was there yet. While inquiring about the whereabouts of the reporters, Cai Yongmei, a female reporter from Hong Kong’s “People” magazine, arrived. We each recognized each other — she had also been present at the rally on May 3rd to conduct interviews. It was better to come early than to to leave anything to chance. And so I hitched a ride with her. We got into the taxi she chartered and started wandering around the city to find teams from the news unit. It was said that they had already been involved in the student demonstration. I heard someone said they were in Xidan. We found Xidan but didn’t see them. After driving around for awhile, we finally got out of the car in front of the Beijing Hotel and prepared to enter the packed square on foot.

This reporter was a particularly kind little woman wearing glasses — it’s strange, the intellectuals in Hong Kong seemed to be much kinder than we were. Whether we engage in class struggle or not makes a big difference indeed. We stood near the guard box at the intersection at the northwest corner of the Great Hall of the People until about two o’clock in the afternoon. I drank every drop of the bottle of water she had brought. I was so embarrassed. It was neither hot nor cold, and the sky was clear. It was a perfect day for marching in the streets. Tiananmen Square was crowded with people, and the various flags and banners would dazzle you. It was like people were drunk and celebrating a grand festival with joy. I stood on a flatbed truck and looked around, waiting impatiently. The owner was a self-employed man, and he repeatedly begged us, “Uncles and brothers, please do me a favor. I have something urgent to do and I need to use this truck.” How could people listen to him? Several young workers yelled at him: “You’ve already done some fucking exercise, and you’re still in a hurry to do your shitty business. Is your conscience like that of a dog?” and so on. The language of the common people is indeed rich and colorful.

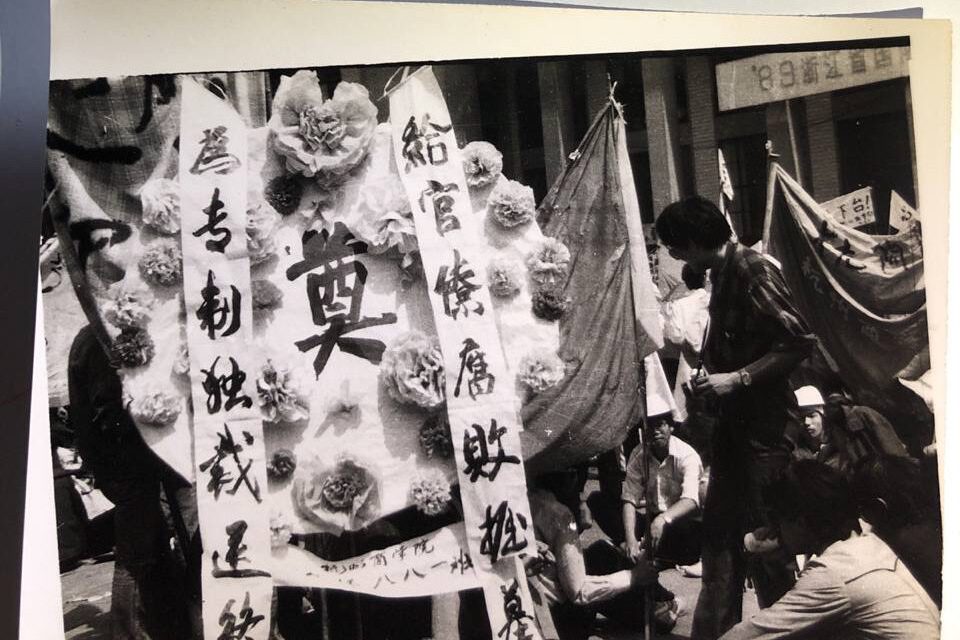

At just about three o’clock, the press parade, sandwiched among the students, slowly entered the square from the direction of West Chang’an Street. This was the first time that all walks of life participated in the demonstration — “this opened up a gap for society to participate in unrest,” as the People’s Daily article on August 17 later put it — so it was extremely eye-catching. The text on the banners was very catchy: “News must tell the truth”; “We have mouths but can’t say what we want to say, and we have pens but can’t write what we want to write,” “Don’t force me to lie,” etc. It spoke to the common sentiment of the press. The reason why the rally on May 3rd was so popular was that reporters and editors were deeply ashamed of the hypocrisy of the news. “Away with shame” was the most emotional and least controversial sentiment among the participants that day.

The enthusiasm of support and praise this parade received from the people was unmatched by subsequent ones. At that time, the masses did not regard demonstrations as a normal event as they later did. People were still dominated by a deep sense of fear, and the press was the most tightly-controlled in history up to that point. So this move by the press was unexpected. Those who participated in this parade would probably never forget the sincerely moving looks of admiration from thousands of college students and other onlookers — including their warm applause and cheers, enthusiastic handshakes and praise. Many people even had tears in their eyes. I lost count of how many people came up to shake hands, say thank you, and give us things to drink. Relationships were completely transformed almost overnight. Originally, when I was growing up in Beijing, I always had the feeling that everyone I met on the street might pounce on you and bite you. I couldn’t go anywhere without getting angry, and I was afraid to go out. I had never seen people’s kindness and beauty expressed so fully as during this “turmoil.” It’s just as the song says, “This is the call of the heart, this is the dedication of love, this is the spring breeze of the world, the source of life, as long as everyone gives a little love, the world will become beautiful.” It was a dream. Although it was short-lived, it left a permanent mark on my heart.

Along the way, the slogan that received the strongest response from the masses was the phrase “Don’t force me to lie.” Whenever this slogan was shouted, it immediately won a wave of thunderous applause and cheers. This was the truth about the so-called “unpopular social unrest,”and anyone who personally experienced this scene will never mistake it for anything else. The parade slowly circled the square, sat silently on the road east of the Great Hall of the People for about 20 minutes, and then walked along Qianmen Street to the front of the Xinhua News Agency. Everyone shouted in unison: “Xinhua News Agency, come out! Xinhua News Agency, come out!” Many people applauded in the windows of the Xinhua News Agency building, but no one actually did come out. I carried the banner about lies with me, and as soon as I got home, I nailed it firmly to the wall of my living room, so passersby outside the window could see it.

In this world, there are some things that are bound to happen, and some are destined not to. Some things may or may not, depending on the circumstances. History is a picture painted with three brushes of different colors: “definitely,” “definitely not,” and “perhaps.” The “mediation meeting” of the United Front Work Department on May 13th that I will talk about below, and other similar efforts, are probably of this latter nature: they could have greatly changed the social and historical process of a certain period, but in the end did not. Looking back at the history before and after June 4th, I still firmly believe that the opinions of the hardliners within the party that led to large-scale violent and bloody conflict did not have to prevail. Even given Deng Xiaoping’s position and the relationship between Deng and Zhao Ziyang, etc., before martial law had been promulgated, the hunger striking students in the square were already somewhat political. Had they had the brains to understand a little bit of strategy and evacuate the square in time, the ending might have been completely different! It is incredible that the entire political process in China at that time could be completely influenced by such a group of inexperienced children.

On May 13th, I went to the printing factory to edit the English manuscript of the fifth-anniversary picture album of our Four Communications. When I returned to the company, my subordinates told me that Tao Siliang (Director of the Sixth Bureau of the United Front Work Department) had called me and asked me to go to the department for a meeting. I do not recall the exact words.

The original intention of this meeting was to gather the views of high-level non-party intellectuals on the current situation. Among the eight or nine people there, I only knew Zheng Yefu and Li Su from the Beijing Academy of Social Sciences. There were two other meetings held at the United Front Department at the same time that day, as well as a dialogue among Hu Qili, Dai Qing and other senior journalists.

After May 4th, I had decided not to get involved. I thought, I am not qualified to engage in politics. I know almost nothing about political practice and theory. I didn’t think my intuition would do any good amid China’s confusing political chaos. In addition, I felt that I had done enough, and could sit back and watch whatever happened with peace of mind. Later, I thought that the reason why despite this I became involved again and again was probably because I couldn’t help myself. The truth is, I am not some “if I can’t do it no one will” type of hero. In fact, my real “engagement with the troubled students” officially began at the “mediation meeting” on May 13th. Therefore, of all the people at this meeting, I was the least informed. I only learned about students going on hunger strike after hearing Tao Siliang talk about it. I can’t remember a word of the nonsense everyone was talking about the current situation, and there’s no need to remember it. Tao Siliang seemed restless. Later, we proposed that the United Front Work Department should come forward to convene student representatives from all walks of life for dialogue and persuade them to stop the hunger strike. Tao Siliang immediately asked Yan Mingfu for instructions. Soon, Yan Mingfu came over from the meeting held by Hu Qili. While discussing the specific methods with us, he asked his subordinates to call the central government, namely Zhao Ziyang, for instructions. The superiors quickly agreed and officially authorized the United Front Work Department to take charge of the matter.

Then Yang Mingfu said that central leaders are very worried about the current situation. Gorbachev’s visit to China is a historic event that will attract worldwide attention. If students still occupy the square at this time, they will inevitably interfere with this major state event and have a very bad international impact. The subjective wishes of young students are good. Demonstrations are nothing to be alarmed about. Xu Simin from Hong Kong once went to the hospital to see me. I said, in my personal opinion, China is currently going through the painful period of transition from a closed society to an open society. Demonstrations should become a normal phenomenon. I am confident about the future. Why are you looking so sad? Of course, solving the problem will take time and we must be brought into line with the rule of law. Demonstrations are a choice when there are no other channels; just don’t be surprised, and get used to it. One must be generous about this and the petition should be accepted. For example, if you want to cross a mountain, the customary method in the past was to blast it with cannons, but you can also use machines to dig tunnels. Some media reports in Hong Kong are unfavorable toward me. Are they going to take me up very high off the ground and then drop me to my death? “The Tiger Report” said that Deng Xiaoping reflected upon three things: anti-liberalization, price breakthroughs, and student unrest, saying that I was the one who raised them. How can this happen? You say that the central government is divided into conservatives and reformers. I disagree with this. The central leadership is unanimous in supporting reform. However, comrades who are not on the front line still have many opinions on many specific issues and practices. To this day, Beijing was still adhering to its original attitude. I thought Beijing must act now. If the students continued to cause trouble, Beijing might take action then and this would lead to full-scale street protests. Let’s put it bluntly: give those who you think are reformers a chance to breathe, otherwise we will all be screwed and have to give up. Please do your work and advise the students to understand the general situation, take it into consideration, and evacuate the square first. Any demands they have can be discussed later and resolved through consultation and dialogue. There is always a process for major decisions, and it is impossible to do if immediately in only two or three days. The development of things often does not depend on people’s subjective wishes. If students continue to cause trouble, they will inevitably regret it in the future.

Frankly, outstanding political leaders like Yan Mingfu are rare among the upper echelons of the CCP. In short, he had a kind of personal charm that could make people willingly do what he asked of them without giving any mandatory orders — just as Wang Juntao said that night, he could move God. What a pity, the upper echelons of the CCP seem to have no tolerance for the existence of such outstanding figures, and are determined to get rid of them as soon as possible — doing things backwards by eliminating the good and leaving the bad. In fact, there don’t need to be too many such people. Even if only one-tenth or one-twentieth of the Communist Party leaders are like this, I’m afraid not many will act to cause trouble. At least there won’t be a big mess. If anyone really wants to overthrow the Communist Party, I advise them to get rid of people like Yan Mingfu first, and don’t be polite about it.

Yan Mingfu requested that the meeting be held with student representatives on the same day, the sooner the better. This seemed impossible. No one knew the students’ situation. They were scattered throughout the city and their whereabouts were unknowable. Who were the representatives? Could the students be represented? Where to find them? We didn’t know anything. Tao Siliang asked, “Who has contact with the students? Who can handle this matter?” No one answered. Everyone looked troubled.

I then said, “Let me give it a try. The big problem is supposedly that we can’t hold the meeting today. But trying to do that is better than doing nothing.” After thinking about it for a while, I suggested that Li Su, Zheng Yefu, and I should divide our personnel into three groups. Zheng Yefu would go to the political and legal affairs department. As for the universities, Li Su went to Beijing Normal University, and I went to Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Renmin University. Li Su repeatedly said that he didn’t know anyone, so how could he find them? Let me advise him, I said. I suggested that he go to Liu Xiaobo and find Wuer Kaixi through him. I also helped him get the call through to Xiaobo, who happened to be at home, and told him to wait there. I told Li Su the address and asked him to go directly to Xiaobo’s house. He insisted that I take him there, and then I could go to Peking University. This made me so impatient.

Yan Mingfu had lunch with us. The meal was so simple that it was almost shabby, not much better than an ordinary working lunch at Sitong. In addition to small talk, he once again emphasized: “You said that there are ‘reformists’ and ‘conservatives’ in the Central Committee. I disagree. The opinions of the Central Committee are consistent and they are all in favor of reform (I thought to myself: you, wise old man, you don’t use diplomatic rhetoric, thank you!). It is wrong for the students to oppose Comrade Deng Xiaoping. If he isn’t there, many things become difficult.”

After lunch, the United Front Work Department assigned three cars to us. Zheng Yefu then went to the University of Political Science and Law. Li Su and I went to Beijing Normal University first. Dai Qing came out just as we were about to leave, and Tao Siliang asked us to take her home. On the way, she asked me if I had ever learned to sing. I replied that it seemed that people were easily deceived by illusions. In fact, I am not that sort, not singing material at all. I told her that one time I went to a furniture store to buy a bookcase, and the salesperson suddenly asked me if I worked in a radio station. I was surprised and quickly said, “No, I am a teacher at Peking University.” She sighed, “What a shame, what a waste!” She thought I was a radio announcer. These are the values of Chinese people: a dignified lecturer at Peking University is far inferior to an ordinary broadcaster.

After we arrived at Beijing Normal University and met Liu Xiaobo, we then went to the tomb of the “March 18th Martyrs” to meet Wuer Kaixi. As I recall we gathered there to to take him to Tiananmen Square. The campus was very lively, with groups of students wearing white stripes on their heads everywhere. Words such as “hunger strike,” “democracy” and “freedom” were written in ink on the cloth strips. But after waiting for a long time, there was no sign of Wuer Kaixi. Accompanying us was a kind-hearted young man named Liang Qingdun. He wrote his name for us but said it was difficult to remember, so we should just call him “Liang Number Two.” This young man was later on the list of the “21 Primary High-Level Autonomous Federation Prisoners.” By now he must be eating gruel in Qincheng Prison.

I got tired of waiting, so I left Xiaobo behind, made an appointment to go back to his house at five o’clock, and took Li Su and Liang Number Two to Peking University. Liang Number Two said that the “Gao Zilian” were holding a joint meeting on the 38th floor and so they had to go quickly. If the meeting broke up, they would not be able to get in touch with them again. From Liang Number Two, we learned that the rebellious students at that time were mainly divided into three major forces: the “Gao Zilian,” the “Dialogue Group” and the “Hunger Strike Group.”

But in the end we were still a step behind. The meeting of the “Gao Zilian” had already dispersed. Fortunately, Liang Number Two bumped into Shao Jiang, a leader of the Peking University Autonomous Student Union. I explained my intention, but Shao Jiang brushed me off, and said something that irritated me a bit. He said: “We don’t care, and certainly don’t want to get involved in any high-level power struggle. The words ‘reformers’ and ‘conservatives’ have nothing to do with us. We were fooled once in 1976, and this time we don’t want to be fooled again. The goal is to establish a democratic system, not to help any side in particular. Besides, the government has no sincerity when we talk with it, and we have given up hope.” This was really a strange thing to say! It seems that my warnings were of no use — I had repeatedly warned the students through various channels that we had to distinguish the reformists from the conservatives, and we needed to bring Deng over, otherwise the student movement would fail.

I couldn’t say much to Shao Jiang at that time, but I had to say this: “You can’t make such a simplistic analogy. Of course, putting a person in power and giving him absolute authority can no longer be done. However, times have changed after all. Why can’t we help the reformers and then monitor and limit them? The key is who controls whom and who is whose tool: is someone the tool of the people, or are the people his tool? When you say that the government has no sincerity in its dialogue, what does this ‘government’ refer to? You should always know that the government is not one person and cannot always agree. If there is no sincerity in dialogue, what will the higher authorities demand we do?”, and so on, attempting to coax and persuade. Li Su also had a sharp tongue and tried to persuade Shao Jiang by every possible manner. Finally, I finally convinced him to take us to Tsinghua University.

Li Su said that he had to go to the High Court, made an appointment to meet at the United Front Work Department in the evening, and said goodbye. I took Liang Number Two and Shao Jiang to Tsinghua University, and after a lot of trouble, I found a student named Zhou Fengsuo. We couldn’t get to the National People’s Congress, so we quickly drove back to Xiaobo’s home at Beijing Normal University. At this time Wuer Kaixi was already sitting there. This was my first time meeting him. He introduced the situation and said that almost all the leaders of the “hunger strike group” and the “China Self-Federation” were in the square. We filled a taxi, Xiaobo called another one, and the group rushed to Tiananmen Square. The car drove to the west side of the square and parked. I asked them to find someone quickly, and then rushed to the United Front Work Department to report the situation. At this time, the representatives of the “dialogue group” that Zheng Yefu found through Wang Juntao, Chen Xiaoping and others had arrived, headed by Xiang Xiaoji. Afterward, I returned to the square and took about ten people, including Wang Dan, Wang Chaohua, Cheng Zhen, and Wuer Kaixi, to the United Front Work Department. It was nearly 7:30.

There were about thirty to forty student representatives from the three parties; Liu Yandong also brought about twenty representatives from the Communist Youth League and the official student union, plus me, Xiaobo, Jun Tao, Min Qi, Chen Xiaoping, Zheng Yefu, Li Su and other intermediaries. There are always 70 to 80 staff members of the United Front Work Department, and the sixth conference room was packed to the brim. After Yan Mingfu came in, he sat at one end of the conference table and gestured for me to sit next to him. I didn’t go over and instead sat at the other end with Liu Xiaobo, Zheng Yefu, and Li Su. Yan Mingfu was obviously unhappy when he saw how close Liu Xiaobo and I were. I was afraid that I had committed a big taboo by bringing Liu Xiaobo here. I thought to myself, I deserved it, now that I have come, let me live in peace. I had no choice but to ask Tao Siliang to forgive me for making my own decision. I need to explain a little here…

(To be continued)

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247818&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.