By: Cai Xia

Source: Radio Free Asia, November 14, 2023

Editor’s note: Cai Xia is the editor of Yibao Chinese. Here she argues that even the amount of self-government that existed before Xi Jinping came to power has been eliminated under his rule, in lieu of a transfer of authority to the Communist Party and to him personally.

Almost a month ago, Li Keqiang’s mysterious death shocked China and the world. On the one hand, a huge wave of mourning broke out among the people, with unprecedented influence and attracting world attention. On the other hand, there was a surprising dead silence within the party. Beyond publishing an official announcement that mimicked almost word for word that of former Chinese prime minister Li Peng’s death in 2019 and the announcement of the cremation of the body, there were almost no commemorative articles issued by the CCP. Even private comments under the official announcement were blocked. The second-in-command of the Communist Party of China (CPC) died under mysterious circumstances, but the truth was nowhere to be found. All this has made a huge impact on and even shocked the CPC. In particular, officials from the top level down are mournful, frightened and uneasy. Everyone feels endangered. The deathly silence within the party is a strange manifestation of this extreme shock.

When the rabbit dies even the fox mourns, and even more we mourn the tragedies of those like us. In the tragic fate of Li Keqiang, many CCP officials vaguely saw their inevitable fate.

Why? First, the institutional evil of the CCP’s totalitarian rule and personal dictatorship has caused the “difficulty” of Premier Li Keqiang, and is also a common dilemma faced by responsible officials in the CCP government system.

After the CCP seized power, party officials were divided into two categories: those involved in party affairs and those involved in government affairs. The party-affairs system manages and controls the entire party; the government-affairs system manages and controls the country and society. The party’s “leadership” firmly controls all the power and resources of the country; the personified embodiment of “party leadership” is that the party committee secretaries at all levels exercise strong and effective control over the relevant people’s congress, the government and the judiciary. It is the general secretary of the Party Central Committee that leads the prime minister; in the provinces, the provincial party secretary leads the governor, and similarly at the county and city levels. In short, party officials are the operators who implement the CCP’s rule, while government officials are the wage earners who preside over that rule. This determines that as long as Xi Jinping wanted to exercise and expand his power, Li Keqiang could not stop him. Li served as Prime Minister for ten years and was very conscientious. Yet his classmates and old friends said things like, “If you stay cautious for ten years, you will accomplish nothing,” and “You will live a miserable life and die a useless person.”

The fact of the matter was that Xi Jinping continued to dismantle the relative independence and integrity of the government-affairs half of the system and usurp the power of Premier Li Keqiang, thereby making it difficult for Li to govern.

Let us review a few episodes:

After ascending to power, Xi Jinping quickly established a number of “leadership groups” in the name of reform and appointed himself as the leader of six of them. Anyone who experienced the Cultural Revolution knows that Xi Jinping was cribbing someone else’s homework — imitating Jiang Qing’s actual manipulation of the “Central Cultural Revolution Leadership Group” during the Cultural Revolution. This time around, in the analogous wording of the 2014 Central Finance and Economics Leadership Group, “The group is at the the top of the pyramid in China’s political leadership system” and “is actually the organization that makes important national economic strategic decisions” [1]. As the “team leader,” Xi reached out to grasp the power of the State Council, squeezed out Li Keqiang, and gradually marginalized him. This group, headed by party leader Xi, is now responsible for major decisions on national economic development. He re-appointed Liu He and excluded Li from the core decision-making circle. This is probably why people in Beijing called Lu Wei, who was once favored by Xi Jinping, the “Internet Czar” and Liu He the “Economic Czar.” Conversely, in the decision-making and implementation of Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road Initiative” and the millennium plan for the “Xiong’an New Area” [a plan for a new city near Beijing that is supposed to house many government offices and hangers-on], people never saw any reports of Li’s involvement.

Li Keqiang’s policy blueprint after becoming Prime Minister was to “promote China’s urbanization in the process of industrialization,” which included the plan he envisioned to promote reform and development. However, in December 2013, Xi Jinping convened the Urbanization Work Conference of the CPC Central Committee in the name of the Party Central Committee, stripping the powers and organizational structure of promoting urbanization originally controlled by Premier Li Keqiang and incorporating them into Xi Jinping’s central “leadership group” system. This actually changed the power and responsibility relationship within the State Council system, and Li was sidelined — even State Council departments are not responsible to the Prime Minister, but directly to Xi, the leader of this CCP-designated “leadership group.”

In February 2018, Xi Jinping’s Central Committee plenary session decided to “systematically and holistically reconstruct the organizational structure and management system” of the party and the state [2]. After more than a year of institutional mergers and adjustments, the government’s important and especially its critical departments were directly placed in the hands of the Party Central Committee.

The first approach is to retain the departments responsible for public- administration functions in the State Council in name, even as key departments, such as the Ministry of Finance, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Audit Office, etc., are actually led and managed by the a CCP central “leadership group” or “Central XX Committee.” The second is to merge government departments that significantly impact the rule of the CCP into the central functional agencies of the party itself. For example, the Ministry of Human Resources was merged into the Organization Department of the party Central Committee; and the State Press and Publication Administration, the Radio and Film Bureau, and China Central Television became subordinate units directly managed by the Central Propaganda Department. The third is to reorganize all the armed forces that were previously dispersed and managed for various reasons by different relevant government departments under the leadership of the Central Military Commission. The Central Military Commission implements the single-person responsibility system of the Chairman of the Military Commission, that is, one person solely controls the military power.

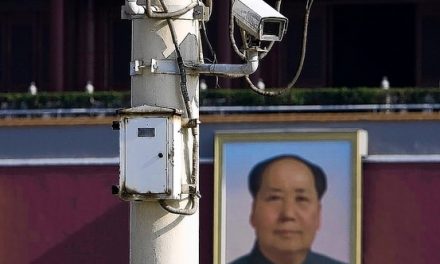

In sum, the party and government institutional changes from 2018 to 2019 demonstrate that Xi Jinping surpassed even Mao Zedong in using the CCP system and its functional agencies to annex actual government operational departments, and inaugurated and formally established a party-state system in which “the party and the state are integrated,” as well as an operating mechanism [3].

Xi Jinping’s three major steps directly decomposed the power of the State Council, and Li Keqiang became the weakest prime minister in the 40 years since 1978. The power of China’s economic decision-making is no longer in the hands of the Prime Minister. The State Council system is no longer the decision-making and operational-implementation center that leads the country’s economic construction. Instead, it has been reduced to an execution system for implementing Xi’s central decision-making. Because of this, it was difficult for Li to propose and implement major decisions related to the country’s economic and social development, and it remains difficult to adjust certain economic and social policies. Even Li’s 2020 initiative to propose a “street stall economy” to alleviate the difficulties people at the bottom have in making a living fell through because of the obstruction and resistance of Cai Qi and other members of Xi Jinping’s gang.

Even so, Li Keqiang strove to promote government reform and economic development to the extent of his ability. He worked tirelessly for ten years to transform government functions and promote reform via “decentralization, regulation and service.” He firmly grasped the requirement of “building a government based on the rule of law,” and promoted reform via “simplifying administration and delegating power, combining delegation and regulation, and optimizing services.” Li himself once said,”In the market, anything can be done without prohibition by law; in government, nothing can be done without authorization by law” [4]. He led all ministries and commissions of the central government and local governments at all levels to clean up and abolish previous government regulations, systems and documents that did not meet the requirements of “delegation, regulation and service.” Over the past ten years, reforms carried out in the name of these objectives achieved remarkable results: central ministries and commissions canceled or adjusted a total of 2,183 administrative-approval requirements; provinces and municipalities canceled or modified 36,986 items; and so two-thirds of the country’s approval requirements were removed. Over ten years, the State Council pushed for tax and fee reductions, canceling 61 different ones and yielding a total tax reduction of 14 trillion yuan, benefiting 1 billion people. The State Council vigorously supported small, medium and micro enterprises and the private economy, and the number of small, medium and micro enterprises nationwide thus increased from 14 million to 52 million households.

To take specific examples, when WeChat first started, relevant government departments did not approve of its release. Li Keqiang withstood the pressure. He said he would take a look at and standardize it, and WeChat was able to begin operations. When the express-delivery industry first developed, some cities did not allow it. Li Keqiang emphasized that new things should not be regulated immediately, and ultimately should be regulated in an “inclusive and prudent” way as much as possible. Today, most people use WeChat and express delivery in their daily lives.

Even more noteworthy, Li Keqiang always did his best to safeguard the interests of the people at the bottom of society, increase people’s incomes, and improve their lives. For example, in his ten years he promoted the construction of affordable housing and the renovation of shantytowns. A total of more than 59 million units of such housing were built, allowing 140 million low-income people with minimum living standards to have a stable place to live. To take another example, there was a large explosion in fhe Tianjin New Area in 2015. Many of the victims were migrant or “temporary” workers. According to past practice, the maximum compensation for each victim was RMB 500,000 to RMB 600,000. It was Prime Minister Li’s decision to defy public opinion and raise compensation to 2 million.

Due to the black-box nature of Chinese politics, these situations are rarely known by the public. Even if people within the system know the inside story, they dare not discuss it casually for their own safety reasons, let alone speak publicly. Based on the aforementioned situation, it would be unfair to Li Keqiang to say that “nothing was accomplished” in ten years. He tried his best to accomplish things, but what he could do was simply incomparable to what a prime minister in a normal country should do.

The difficulties faced by the prime minister and emanating from this evil system are inherent in a communist totalitarian country where the party leads everything. This dilemma has been further aggravated by Xi Jinping’s personal dictatorship that he has built since coming to power. In this regard, Li Keqiang’s difficulty has not been his alone, but is a dilemma in which actual public officials who are all at some level the second-in-command within the CCP system are generally trapped.

Within the CCP system, all party diktats must be obeyed. After Xi Jinping came to power, he took several steps to weaken the power of the State Council and the Prime Minister, something done consistently from top to bottom throughout the system. From the central to the local level, the power of party secretaries has been greatly expanded, and the power of local governments has been continuously reduced. The independent government administration required for public management and public services does not actually exist.

At the same time, the party leading everything in practice means the party controlling everything. The personification of the Party — its secretary-general — must control all resources of political power, the core of which are those involving financial rights and human rights more generally. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China has always emphasized that “the Party manages cadres and manages talents,” and specific affairs have also been handled by the Organization Department of the Central Committee. In the past, the CCP was still characterized by democratic centralism and the right to appoint important officials, and the Standing Committee had a collective discussion system (although the opinions of the secretary often carried much greater weight). But in the Xi Jinping era, the more important officials are appointed directly, Xi personally approves personnel decisions, and the prime minister has almost no role to play in questions of human rights. Similarly, at the local level the nominally responsible official has almost no role to play in human rights, and even if he participates, things must be decided by the party secretary. In essence, party secretaries at all levels hold the fate of given officials in their hands, and these officials all bow their heads to and obey the orders of party secretaries.

As for financial power, Xi Jinping’s appointment as the leader of the Central Financial and Economic Leading Group means that he has gained control of it. And so similarly, in addition to official government ministers, the core personnel of the “secretary’s circle” at the local level also include the party director of the finance department. Only the secretary and the director of finance know the financial state of the relevant local government. Whether the officials such as provincial governors and mayors really know how much money is available in local government finances depends on their relationship with the party secretary. Under such circumstances, it is difficult for the “second in command,” the official head of government, to handle administrative affairs independently, let alone have decision-making power over major public affairs.

And thus China was fated to fall into the current situation, in which some public official nominally decides, but power is actually held by the party leader. And so all political achievements are first recorded in the name of the true “maximum leader,” in whose shadow the nominal decision-maker can only live. If the official has strong abilities and high standards, he will still attract the negative attention of some of these maximum leaders if he accomplishes something, for fear that the official’s achievements will overshadow that of their master. Local propaganda agencies must carefully position the news reports and photos of the de facto first and second leaders in local newspapers, so that the “second leader” does not overshadow the “first leader.”

Whether the de facto subordinate, the official, can be promoted or even successfully remain in his position depends to a certain extent on the degree of humiliation and courtesy he shows to the de facto first-in-command. “What’s his rating?” in this regard is what is asked. This makes the de facto second in command like a little daughter-in-law, who has to accompany her mother-in-law everywhere and be very careful, which is naturally very frustrating. However, when an incident occurs or is investigated by superiors, the de jure executive-branch government officials are the first to be scapegoated. When the severity of an accident or problem is not enough to calm the situation by simply taking putative responsibility away from government department personnel, then it is inevitable that they will take the blame. All these factors determine that there are widespread conflicts between the de facto first and second leaders within the CCP system. The actual content of the so-called emphasis on “unity” within the CCP is disunity among these leaders.

These events are invisible to outsiders and discussing them taboo to people within the system. Li Keqiang’s sudden and violent death unexpectedly triggered a wave of condolences among the people and various evaluations of him. Objectively speaking, the public’s evaluation of Li is not high. Yet this kind of low and even disrespectful evaluation coexists with the outpouring of mourning, which seems quite strange. What is the reason? It is indeed the capacity to lean on peers who have suffered the same fate that finally gave an outlet through which to vent individuals’ strong dissatisfaction with Xi Jinping’s perverse policies.

On the other hand, people’s evaluation of Li Keqiang’s “achieving nothing in ten years” has added to the long-standing grievances of and helplessness felt by Chinese government officials. Li’s situation was actually a concentrated reflection of their own. Under the current system of the Chinese Communist Party, any official who hopes to do good and accomplish things for the Chinese people is basically unable to do so. Even if they can get off this ship to nowhere and disembark safely, they will still end up doing nothing, then dying of exhaustion.

(End, part 1)

- 中国共产党新闻网:“中央财经领导小组的变迁”,(China Communist Party News Network: “Changes in the Central Financial and Economic Leading Group,”) 6/25/2014, renshi.people.com.cn

- 習近平 ,人民日報2019年7月6日1版 (Xi Jinping, People’s Daily, July 6, 2019 first edition)

- During the Mao Zedong period, the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese government were on the surface two systems of their own. The party’s control of the government was achieved by dispatching “party groups” to government departments. Therefore, Chinese society during the Mao period had a three-layered structure from top to bottom: Party-Government-Society. The Party stood above the government, and the state stood above society. Xi Jinping’s 2018 reform of party and state institutions was to use three tools to support the government: using the Central Leading Group (the Central Leadership Group. This group was gradually changed to the “Central Committee” after the 19th and 20th National Congress to control the government’s economic and fiscal decision-making and financial-management power; using party agencies to directly annex government departments to control government personnel powers and changing jurisdiction over the armed forces. Originally, part of China’s armed forces was under the jurisdiction of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission — armed police, special police, industrial police (forest police, water and electricity police, gold police, border police, fire police, railway police, etc. Only the People’s Liberation Army, as a national defense force, was under the control of the Central Military Commission. After the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, all armed forces were put under the control of the Central Military Commission. The Central Military Commission implemented the Chairman of the Military Commission responsibility system, that is, all armed forces were placed under the control of Xi Jinping.

- Li Keqiang, remarks at a press conference on March 15, 2014.

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247650&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.