By Hu Fayun

April 2010 First published on Sina Blog (original article since deleted). The article is reprinted from Huaxia Express

Note: The article below is a remembrance, by someone who knew her, of Lin Zhao (1932-1968). Born under the Republic of China, she became a communist as a teenager, and was outspoken during the 100 Flowers Movement, in 1956-1957, in which people were encouraged to speak up about the CCP’s flaws. She spoke up and was arrested in 1957, and after more years of dissidence and persecution was eventually executed without any warning in 1968, during the Cultural Revolution. Since 1949 there have of course been countless Lin Zhaos in China.

A Chinese language documentary about her life, whose title in English is In Search of Lin Zhao’s Soul (link has English subtitles) was released in a different China, in 2004. An English-language movie drama, “5-cent Life,” was made about her by director Phoebe Liu, and released in the U.S. in 2019. The title refers to the fact that when Lin Zhao was told she was to be executed, she had to pay for the bullet.

I have long felt there are some words I need to speak.

Only after I started to write did I realize that the words available to me were so limited.

Each one of us alive, especially every man, has been powerless to say anything to you.

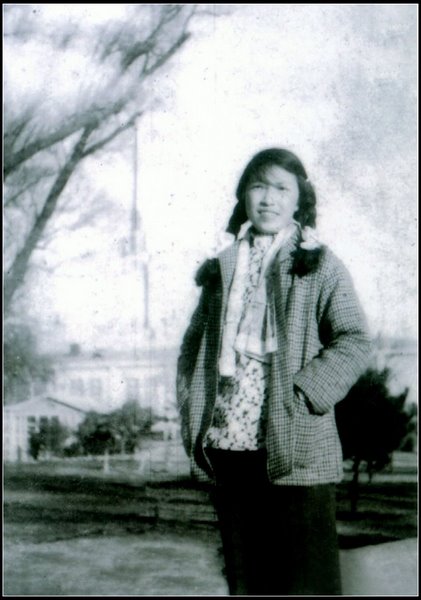

I used to look for your photos everywhere. How I wanted to see them, the eyes of a Jiangnan woman, a mournful woman whom we didn’t want to say goodbye to, so desolate in her loneliness, the silhouette of a saint trapped in hell, a final glimpse of this senseless world before the guns were fired, all this I couldn’t understand. In the past, many criminals had to leave behind photos before being executed. So it was for assassins, robbers, war criminals, the Boxers, Fang Zhimin, Li Dazhao… But, for you, nothing. They destroyed you so completely that even your bones didn’t remain. I don’t think it was because they were afraid. They were already so confident at that time that the greatest revolution in human history was about to be realized in their hands. They were just driven by hatred, scorn and contempt. Like a cat that has had enough of playing with a mouse and then eats the fur. All of them were this way, even the leader of the country.

The first bites were devoured on that evil night in 1957. After that, only your youthful face remained in our memory. Your naive, inquiring, or maybe romantic, passionate eyes, unintentionally become the most powerful mirror in the world.

Actually, before that dark night, you had done nothing. You had nothing but fiery, if unrequited, love for that young “Republic.” You joined the Communist Party at the age of 16 and were blacklisted by the [Republic of China] City Defense Command. Because you did not evacuate with other comrades, you severed ties with the party organization. This incident became your deep regret. But you rejoined the party. On behalf of an intoxicating ideal, you even made a poisonous oath to your mother that “you will never again be in touch with each other in life, and you will never be filial after her death.” You entered the Party’s Sunan Journalism College, you participated in the land reform, and worked hard to sharpen your tender heart to be as hard as steel. You were admitted to Peking University with the first rank in the liberal arts for all of Jiangsu Province. You were like a lark, singing to the leader, singing to the Party. If there had not been that dark night, that sudden fall, your abundant talent, enthusiasm and persistence would have been enough to make you the most dazzling singer in Red China.

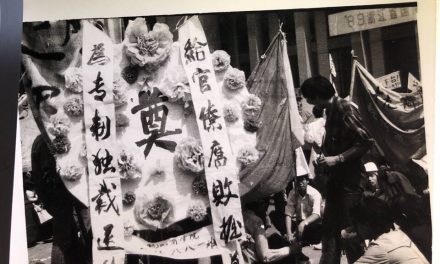

Actually, before that dark night, you had done nothing. Several students who who raised contrary voices were already being besieged, humiliated. You could choose to go away quietly, to be a bystander in the dark, an anonymous parrot, as many, many people have been doing for a very long time — even today people behave this way. What kind of incredible power must it have been that suddenly severed the seemingly unbreakable bond between you and the red utopia, making you jump onto that dining table amidst the carnival of the crowd, and in an instant your voice turning the noise of the sea into silence: “What kind of meeting is this tonight? Is this a conversation or a struggle session? There is no need for a struggle session here. Aren’t we asking for opinions from outsiders? If people don’t offer any, they have to be mobilized repeatedly to do so. But if people do offer their views, why are you so angry?” And then a scary voice comes from the crowd, asking “Who are you? What’s your name?” You respond: “Who are you? What qualifications do you have to ask me this question? Are you a public prosecutor? Or a plainclothes spy? I can tell you, it doesn’t matter. Wu Song [a hero from a classic Chinese novel] killed someone, but it was written that the killer had beaten Wu Song, and of course I haven’t killed anyone yet. You need to remember, my name is Lin Zhao. [Referring to the two characters in her name]: Lin, the forest, and Zhao, a sword above a mouth!”

Before that dark night, you weren’t their target, and you even considered the value of having discussions with some of the “rightists” with whom you disagreed. And when the storm was about to come, you still could have chosen the safe path before others, since you knew what was coming. However, a small seed deep in your heart, a seed that that had been buried under a mountain by a powerful revolutionary ideology, suddenly blossomed at this moment — the seed of dignity and conscience. You couldn’t bear to see other people’s dignity being desecrated, and you can’t bear to see other people’s conscience being annihilated.

Chen Aiwen, a Peking University “rightist,” later recalled: “Almost all rightists had been investigated. The only one I know who refused to self-criticize was Lin Zhao. Not only did she not self-criticize, but she also publicly objected at the meeting. Someone asked her: ‘Tell me, what is your view of things?’ She replied: ‘My view of things is very simple, everyone should be equal, free, kind, and live harmoniously. Don’t accuse people like this!’”

In this way, such simple common sense from a woman bombarded this red utopia built on countless grand discourses.

This was an almost unimaginable thing.

From this moment on, you walked a path of no return.

Many people engaged in the self-criticism, pleaded guilty. Your dignity caused you to reject such debasing self-torture. So many people in the end survived, but in your nobility you saw that it was better to die as a shattered piece of jade than an intact piece of pottery. Almost everyone chose to silence themselves, to leave the palace, but you sang in full voice to your last breath…

We have no sense of history, every generation is severed from the past. Thus each time we must repeat the darkness, ignorance, humiliation and evil of our forebears.

In isolation behind prison walls, someone destined to be the greatest saint in Chinese history died anonymously, like a bright star that emerges in the morning but whose traces can still be seen in the evening dew.

Save for the executioner, no one heard the gunshot on April 29, 1968. Not long after my 19th birthday that day, I was touring the ancient area of Jingchu with a middle-school students’ so-called literary and art propaganda team.

We sang the poems of the great leaders. “With power to spare we must pursue the tottering foe, and not ape Hsiang Yu the conqueror seeking idle fame” [from a poem written by Mao Zedong commemorating the CCP conquest of Nanjing in 1949]. We didn’t know that you had written your own poem: “Only for the public and the common people of the country, not for the emperors ruling over the mountains and rivers.” We danced “In sailing the seas we rely on the Great Helmsman,” and we didn’t know that you were dancing with your life: “Arise! Abandon those holy books and divine words, smash all the idols and incense lamps, trample them underfoot, go to Olympus, and reclaim the destiny of being free!” We played “Beloved Chairman Mao, you are the red sun in our hearts,” and we didn’t know that in a medieval dungeon, blood flowed from your veins, and then you used it and your fingers, hairpins and toothbrush handles to paint some light just before dawn, when it is darkest.

Although we also had doubts, trembling, and youthful confusion and dreams, your own vast ideal, which once made you tremble, is still the sunshine in our hearts. We didn’t know that at that moment one of the most painful and dark events in Chinese history had occurred. But real rays of dawn were found in your heart, and they departed with you.

We have no history, every generation has been severed from the past. Today, these nineteen-year-old children don’t know that around the time they were born, there were similar gunshots in Tiananmen Square.

Looking at my diary from 1968, I see that on April 29 of that year, I was performing in Gong’an County, which is famous for its writers, the three Yuan brothers. During those days when I was running around, I would write down words like these almost every day: “Rehearsed in the morning, then walked seven or eight miles in the evening to perform for the poor and lower-middle peasants. Then I walked home in the rain. The rain was dense, the road slippery, the sky black…But everyone competed to carry their instruments and props, like the Red Army’s Long March — good exercise.” “I remember you all from those days. Below the stage, I often saw or heard your honest, sincere, longing eyes, some familiar faces, those bursts of sincere laughter, yes I remember you. You delivered tea to our hands and the food on the stage. Some ordinary but rich home-cooked meals were the produce of your sincere red hearts. In the wind, in the rain, we insisted on performing. The sky was the curtain, and the rice field the stage. In this way, we strived again and again, singing and dancing, surpassing what was on the urban stages.” “Performed at the Shashi People’s Theater at night. The wind was blowing, and Shashi was full of storms. In the evening, returning to our camp against the wind and sand, like an expedition team returning triumphantly. This kind of life of struggle is preferred by anyone, it is better than calm winds and waves. It is late at night, and there are still trees and gales outside the window …” “Arrived at Honghu Lake at 6 in the morning. In the evening, everyone discussed whether to continue on or return to Han. The debate was fierce. It seemed that everyone was confused, emotional. I insisted on performing. The people need us.” “The wind and rain have been howling for several days, we can’t go anywhere. But the field is an emerald-green world, and it is as if we are trapped on an isolated island in a green lake. Today is a day of rest, and after this we can’t rest anymore. The next step may be Jingzhou, life is not stressful, work hard, study! The child says that on the river, the dead seem to still be with us…Outside the window, the sound of wind and rain. Inside it, the sounds of people, of reading books.”

……

Reading these diaries from 40 years ago, I remembered that when you were in Sunan Journalism College, you went to the countryside to participate in the land reform, and you also wrote similar-sounding words. You also happened to be 19 at the time, in the mood for love, beautiful, innocent, passionate, and so impulsive, so gullible.

In your letter to your friend Ni Jingxiong you wrote, “Everyone knows that land reform is an important part of consolidating our motherland. Our position is one requiring struggle. If you think about it this way, then if you don’t work hard, how can you be worthy of the Party and the people?” “Now I really have nothing I feel I need to ask for, even my affection for my family is much weaker. I only have a red star in my heart, I know that while I am here, he (Mao Zedong) is in Beijing or Moscow, and every time I think of him, I feel excited.”

A work team placed a landlord in a water tank in winter, and he howled all night in the cold. You called this a “cold pleasure” and said “my feelings of hatred of the landlord are still the same, as are my feelings of patriotism. This kind of love and hate is also the strength of my progress. When I hear stories of the heroic fighting of the volunteers, and poke my head up from the battle clouds written on the paper, and then look at the quiet and beautiful spring fields outside my window, I feel more responsible for the work I am doing. Such a motherland, I must not let it suffer…”

How does such a colorful revolutionary fairy tale unintentionally collide with human nature, dignity, freedom, morality, sincerity and love? How can these simplest and most basic principles cause everything to collapse in an instant? From land reform to the anti-rightist movement, after just a few years, how could that dazzling fairy tale turn into this black nightmare? It clung to you, suppressed you, ate at you. From that time began your 11 years of heart-scalding purgatory, finally ending in your reaching nirvana, as you become a phoenix bathed in fire.

How did such a long and difficult physical and spiritual torture befall such a frail, beautiful woman? In the end, it had to be a shocking way of seeing the world that led to the most shameless and brutal murder of the twentieth century.

I know there are many heroines in the world, ancient and modern, Chinese and foreign, who set foot on the road of no return, to the later admiration of the world. Even Qiu Jin [a feminist and proto-communist revolutionary executed by the Qing in 1907], with whom you are often compared, knew very well that “The blood shed will be deeply cherished, and even if scattered over the ground, it can still turn into a sea of green.” She could also see that the day after she was struck down, newspapers across the country would bring her back to life, and she would live forever. And yet forty years after your death, few dare speak the name Lin Zhao.

Qiu Jin also said, in a poem anticipating her own death: “Drunken dreams by comrades in pain are no better than fainting.” For Lin Zhao sixty years later, it should be “Drunken dreams by comrades in pain are is no better than going mad.”

There is also the classic red character Sister Jiang, whom we used to be as familiar with as our own relatives—Jiang Zhuyun. In the Zhazidong Concentration Camp, the “most terrifying devil’s den,” it was said she could still study Mao Zedong’s “On New Democracy” with her comrades in arms. They could then have a party together, mourn dead comrades together, and embroider for the People’s Republic she dedicated herself to. She could quickly put together a five-star red flag on the spur of the moment. She could still calmly put on her beautiful blue cheongsam and a bright red sweater, comb her hair without a strand out of place, and then to a crowd sing “Don’t say goodbye with tears” [as portrayed in a film and opera from the 1960s in which Jiang is a character]…

You were taken to the execution ground from a hospital bed with an IV drip. A group of men with guns rushed in and said to you righteously: “Your end is here!” You asked for a change of clothes, were denied, and were taken away “like a chicken grabbed by a hawk.” There was no send-off, no singing, and no tears. This is the most obscene atrocity that this man’s world has committed against a woman — a knowledgeable woman who had never used violence — for thousands of years. And before you were killed, they even instigated female prisoners to strip you naked for their entertainment.

So you bore the double burden of darkness and misery — the darkness of tyranny and in people’s hearts, and the misery of being murdered by the devil and of being abandoned by the masses. I think, even had you been generously allowed to walk along the long street in chains and sing elegiac songs, passers-by and onlookers would only spit at and insult you. A secret execution in the suburbs was really a final favor to you.

In the countryside of Jingchu, ten years after I wrote those lovely youthful words, that is, ten years after your suffering, I also became an “active counter-revolutionary.” This Arthurian pain has tortured generations of young men and women.

We have no history, every generation is severed from the past. And every generation is so lonely. No one does, nor is it possible to, pass down the bloody thinking and bloody lessons of our predecessors. No one, as the Czech writer Fucik [a communist journalist executed by the Nazis in 1943] cried out with tears when walking towards the gallows: “You good people, I love you, but you must be vigilant!”

When I read the song you wrote to your lover during your suffering, I felt that you wrote it to me, or I wrote it to you: “I miss you on this stormy night, in the night outside my window the wind is howling, the raindrops are falling, but my heart flies out to seek you…”

On the tenth anniversary of your death, while in captivity myself I also wrote a song for my lover. The sheet music is still there, already yellowed and brittle, and I pasted it on a piece of hard paper. The title of the song is “My dove, where are you?”:

“Dove, my dove, where are you?

Where are you?

Through the vast clouds and rain, I pursue any trace of you.

Where are you flying when the morning fog dissipates? Where do you hide when the heavy rain hits?

Where do you sing when the sunset glows red?

When the moon rises where do you perch?

O my dove, my dove, may your heart be more beautiful, may your wings be stronger, may you in this vast world fly ever in my heart.”

I signed it in April 1978.

I am luckier than you. If it can be said that you happened to live in the darkest period, ten years later it would be the end of their strength. More importantly, when I walked beyond the big wall, my dove had already landed on my shoulders, and the tribulations allowed me to reap the most precious love in the world, forever. I once thought that even if I died at that moment, I would depart with a smile. Before I walked beyond the big wall, I stole out and we held a secret wedding. We wrote a few words on the wedding photos taken that day, “Smile behind the big wall,” and we genuinely smiled, smiled proudly. If we can ever have such a smile, this life is enough.

Later, when I read the passage you wrote in blood in Shanghai’s Tilanqiao Prison, my heart ached—is it necessary for every generation of our young people to make the same heart-piercing cry? If we had heard such a voice in 1966, what would we do? Would you too cry “Long live…” in Tiananmen Square until you passed out, and then carry a heavy bag on your back through the cold winter of 1968, and embark on a long, slow journey? Would you too torture those gray-haired teachers to death in that harsh summer, and then after more than ten years, having been dragged down by your family, embark again on the hard road to school? Would you still sing “Vow to wipe out the reactionaries!” and “We must liberate the two-thirds of the people of the world who are suffering!”, only to find out that there were actually only a few devastated places left in the world, and our motherland was among them?…

These words of a cuckoo crying blood [a Chinese metaphor evoking extreme grief, a cuckoo crying day and night until blood comes out]: “How is this not our blood? Our innocence, childishness, integrity, kindness, pure heart and passionate temperament are used insidiously, wanting to instigate us to act. And when we grew up a bit, and became aware of the absurdity and cruelty of reality, when we began to demand our due democratic rights, we were persecuted, tortured and suppressed to an unprecedented degree. How is this not our blood? Our youth, love, friendship, studies, career, aspirations, ideals, happiness, freedom, everything in our lives, everything in our person, was almost completely destroyed by and buried under the foul and unbearable crimes committed under the rule of this filthy and terroristic totalitarian system. How is this not our blood?”

I love your words in this way, I love your seemingly heaven-sent poetry of genius, including your improvisational works, spun out off the top of your head. I love your words, your demeanor so much. If there is one person who could be called a poet in the long darkness after 1957, then this crown should be placed on your head. All those who have harmed and shamed you should bear lifelong guilt for their reckless waste of your gifts.

At this point, I want to say, Lin Zhao, how can we not love you, and yet how should we love you? You have shamed everyone from an entire era. You have shamed all Chinese people, especially the men among them. Because of your existence, this nation can no longer hold its head high.

Unless there comes a day when you stand on the square again, in the park. Let us then point to that white statue and say to our children, because of her, we still have a ray of hope, even in our darkest hours.

Watching martial-arts movies, with their characters wearing ancient costumes those lonely heroines in the most dangerous moments are always rescued by knights. Even if the heroine dies, there is a warm and sad embrace to let her sleep peacefully, and men’s tears dripping on her pale face. In all eras, the victim has a kind of final happiness. She knows what she has, and even if she is on the way to be executed she can see people’s admiring eyes. You didn’t have any of this. In your last days, you were accompanied by a group of robot-like men, carnival women and finally female prisoners who followed behind them. They all took pleasure in torturing you. At that moment, no one in this world would do anything for you.

The era of knights wielding swords had passed, but the era of citizens had not yet come. The chivalry of previous days had collapsed, but the imperial court was still there. Therefore, you were doomed to walk alone, to suffer more misfortune than the heroines of any era. You could never expect anyone to save you, even to give you that last trace of love and warmth, that last embrace.

From those hazy feelings of the spring breezes to the willows by that nameless lake, to your departure from that room in Tilanqiao Prison, in this long song of your life, despite its brevity, there were a few times, hidden or obvious, that seemed like the first ripples of love or friendship. I know that a woman like you, exuberant, sensitive and full of life, should have discovered the spring rivers and spring rains of love. You were deprived even of the natural rights that flowers, birds, caterpillars and grasses should have. In addition to the imperious domination and the cruelty of our times, the person destroyed by fear and guilt is also no longer able to embrace the beauty of this world, the great love for the past and the present.

Now that those of us who managed to survive have lived to an age when we can look back on the past, the men who were with you back then are already gray-haired, but they still have their melancholy of youth, and they can no longer do anything for you.

Shen Zeyi [a poet, and classmate of Lin Zhao at Peking University in the late 1950s]:

One of the authors of the poem “The Time has Come,” a work that led to bloodshed. When he was targeted on the night of May 19, 1957, Lin Zhao jumped on the dining table to cheer him on, and changed the trajectory of his life. Decades later he recalled: “The entire anti-rightist movement had come to an end, and hundreds of rightists had been beaten. I went to a small shop in Haidian outside the south school gate to have breakfast. I opened the curtain and looked over it. Lin Zhao was eating there, surrounded by Peking University students. We couldn’t talk. She raised her head and looked at me. I glanced at her, and then we looked at each other indifferently. This was a farewell, but I never imagined it would be our last farewell in this life.

Gan Cui [classmate of Lin Zhao at both Peking University and Renminbi University, for a time her boyfriend and later someone who did time in the laogai system]:

After Lin Zhao was labeled as a rightist, she was sent to the library of Renmin University for labor reform, where the two met and fell in love. He later said: “Someone from the organization talked to me and said that you two rightists cannot fall in love…But the more we are not allowed to fall in love, the more we talk about her and my characters, and we decided ‘We will show you,’ and we consciously held hands in front of the men and women walking around the campus of Renmin University…When I went to file our (marriage application report), what did I get? The secretary of the general party branch said: You two rightists can’t get married! So since he wouldn’t approve it, there was no way.

Liu Faqing [also condemned at Peking University as a rightist, later exiled to Gansu, where he endured (but survived, with Lin Zhao’s help) the Great Leap Forward famine]:

A cowherd boy from the mountainous area of eastern Guangdong who was often “ashamed of himself” in front of Lin Zhao, he was about to starve to death while undergoing labor reform in the Northwest, and had been a classmate at Peking University who [during the famine, while exiled] received a 35-jin national food stamp from Lin Zhao. Many years later, he said: “After I became a rightist, I seemed to fall from the clouds into the bottomless abyss of hell, immersed in sorrow and regret, and was isolated to the maximum degree…I was sad, I regretted things. I wailed loudly, I bit my own fingers, pulled my hair, fell into endless pain and couldn’t extricate myself. One day at around 5:00 P.M., I was walking with my head down, when someone suddenly shouted in a low voice by the school gate: ‘Where is the rightist Liu Faqing?’ ‘Don’t kid me, I want to go back to school,’ I replied sadly. Lin Zhao suddenly raised her voice and said ‘What are you doing here? Going to have dinner?’ ‘No…I can hardly eat recently. Besides, it’s still early and the dining room is not open.’ I saw a few smiles in her bright eyes. With a very teasing expression, she answered directly and a bit sheepishly, ‘Let’s go! Let’s go out to dinner. My treat.’ Her voice was quiet, but clear.”

“‘I’m not hungry, I don’t want to eat.’”

“‘Come on! You have to eat, you need a full stomach. Aren’t you hungry? Well, then you have got to go with me.’”

“She seemed to be an irresistible force. I looked around and didn’t see any ‘wolf-like eyes,’ so I turned and followed her. When we came out of the cafeteria, it was already dusk. The afterglow of the setting sun dyed the campus of Peking University, and the rosy clouds were burning fiercely on West Mountain. Off in the distance, the twilight was hazy, the breeze was blowing gently, and the leaves of poplar trees were rustling. The summer heat in Beijing had begun to recede, and the refreshing coolness unique to the night to descend. Lin Zhao suddenly stopped and said, ‘Hey, let’s go to the Summer Palace.’ The Summer Palace was only two stops away, and it only cost 5 cents by bus. In the evening, there are few tourists there, and the vast expanse of blue waves of Kunming Lake, the quietness of the winding paths of Longevity Hill, and the rich fragrance of exotic flowers and trees—ah, how poetic and picturesque! This was a good time to relax in the garden. I briefly thought about it, but said: ‘Forget it, it’s getting late, let’s go back to campus!’ The reason why I didn’t go to the Summer Palace was not because I lost all my sense of beauty, nor entirely because I wanted to completely avoid the suspicion of ‘melon fields and plums’ gossip, Instead, we were afraid of being suspected of some secret ‘conspiracy’ because we were seen together, which would cause unnecessary and even unpredictable consequences before we were about to separate. Lin Zhao glanced at me, as if she wanted to say something, but kept silent. After entering the school gate, we each went our own ways…I didn’t say goodbye to her when I left Beijing. And unexpectedly, this separation turned out to be eternal!”

An unnamed prison doctor:

This prison doctor was one of the few people in that dark abyss who silently sympathized with Lin Zhao. He diagnosed and treated her during the many times she was hospitalized. Once she came to the doctor because she was coughing up blood from her respiratory tract, she had lost almost seventy pounds, and he barely recognized her. He said to her quietly, “Oh no, what is this!” Lin Zhao only replied softly, “I’d rather the jade be broken.”

He recalled the scene when Lin Zhao was taken away from the hospital on the day she was shot. In the morning, a few armed men rushed into the ward, forcibly pulled her up from the bed, even though she was receiving glucose, and shouted: “You unrepentant counter-revolutionary, your end is here!” Lin Zhao calmly asked for a change of clothes, but this too was rejected, and then she was carried away like a chicken grabbed by a hawk. When she left, she said to the nurse: “Please say goodbye to Doctor X.” At this time, Doctor X was next to Lin Zhao’s ward, thinking to himself. “I dare not come out, trembling like this.” He told Peng Lingfan that he had been a prison doctor all his life, and he had never seen a patient taken away for execution like this.

Zhang Yuanxun:

On that historic night of May 19, Lin Zhao had once defended colleagues from the editorial department of the Peking University publication “Red Mansion.” At the moment when he and Shen Zeyi suffered their catastrophe, Lin Zhao said loudly at the dinner table, “We should talk about Yuanxun. He is not a party member, not even a member of the group. That he wrote such a poem, does it merit these people’s anger and attacks?”

In May 1966, Zhang Yuanxun was released from prison and went to Shanghai Tilanqiao Prison to meet Lin Zhao in the name of being her fiancé. He was the last acquaintance from Peking University who saw her. A reunion of old friends destined to be separated both in life and death would soon pass in inextricable sorrow, heroism and pain.

Zhang Yuanxun recalled: “The time to part was approaching, and it was really difficult to look at each other and say goodbye! At this time, Lin Zhao said to me: ‘Come here, come to my side.’ She stood up and motioned with her hand to me, asking me to walk from one side of the table to the other. Approaching her, I hesitated. Then, the correctional cadre, again showing understanding and concern, said to me, ‘Yes! Yes! You can go over to her.’ So I went around the table and sat opposite Lin Zhao, and as we were close together we really had a heartfelt conversation. Lin Zhao was in deep thought, and finally said: ‘I give you this poem.’ So she recited it softly, with a round and sonorous rhyme:

‘Laughing together on the Lanqiao well platform

The most worrying thing is the end of the world

The ancient river drifts away, its sound vanishing

The gentleman in his awe forgets living and dying

I still remember the farewell on that winter’s night in Haidian

Swallowing my voice for nine years, and then to die such a death

The morning sun does not put an end to the wind and the rain

In the next life I will seek out the extinguished flame’”

“She said these words slowly, one sentence at a time. She then said, ‘Poetry expresses our ambition! At this moment, I don’t have time to think too much about our sickness, just to leave my true feelings and verdant blood for eternity. I can die a quick death, but my soul will not be scattered to the winds!…If one day you are allowed to speak, don’t forget to tell those who live: there was once a Lin Zhao, whom they killed because she loved them too much! What I hated most was the deception, and I finally realized that we were indeed deceived, countless numbers of us.’ She rummaged through her old cloth pocket, and finally took out something that looked like a piece of paper and handed it to me. It was a sailboat made of transparent paper, wrapped in sugar cubes and folded into strips narrower than leek leaves. I took off a hero’s gold pen in my own pocket, handed it to her, and said, ‘I give this to you.’ She took it in her hand and was happy, but suddenly she saw the words ‘Grasp revolution, promote production’ engraved on the pen. She immediately changed her face, no longer happy, and with a flick of her wrist she threw the pen on the table and said: ‘I don’t want it.’'”

……

These were the several emotional scenes that I read about Lin Zhao, a great sage, great philosopher, brave and wise, that were recorded over her 36 years of life. How I wished a passionate poet could walk up to Lin Zhao in front of everyone in that small restaurant, sit down calmly, caress Lin Zhao’s delicate hand and say: ‘You are a true poem’; I wished even more that the person who fell in love with Lin Zhao could have an unexpected wedding to this tender woman on a stormy night, with no need to pray for that wedding license; and that that evening, I was able to walk side by side with Lin Zhao by the Kunming Lake until the moon was shining in the sky. How I wished that the prison doctor, who still retained his conscience, had rushed over from the next ward when he heard Lin Zhao’s last farewell, and stayed with the dying woman, with them holding hands and looking at each other, him sending her on her final road with warmth and respect. How I wish that the man who visited Lin Zhao with great courage and deep emotions as her fiancé would hold her tightly in his arms at the time of their farewell, and whisper in her ear, “See you in heaven!” Amid the tugging and shoving of the prison guards, I wish that Lin Zhao had also been properly given a farewell poem…Let a woman who suffered the most severe suffering in the 20th century travel to the other side and be sent off warmly, with love.

No, no, none of these wishes, none of these dreams came true. There was no stronger male arm that could surround her and let her cry heartily, let all her little girl’s grievances and pains flow out with the tears, to wash away all the bitterness and loneliness in her heart.

Throughout the thousands of miles of Red China, it is fated that there will be no earth-shattering drama of these events! There is no leading actor who could play opposite Lin Zhao. This is the real tragedy.

The gunshot on April 29, 1968 took Lin Zhao from us at the age of 36, forever. Oh, you beautiful and lonely Lin Zhao.

You are a child of God who had the misfortune of falling into this land. Evil and cowardice nailed you to your cross, but you can still in a way live forever.

【转载请加上出处和链接:https://yibaochina.com/?p=250220/】

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/2023/05/04/lin-zhao-how-we-love-you/ before the text when reprinting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.