Editor’s note: the following appeared in Yibao Chinese, on February 12, 2023, at https://yibaochina.com/?p=249437, after having been found on WeChat, from where it was quickly removed. It refers to an appalling case in Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, in which residents of a residential tower reported a fire, but anti-COVID rules kept firefighters from rescuing them. The author of the piece is anonymous.

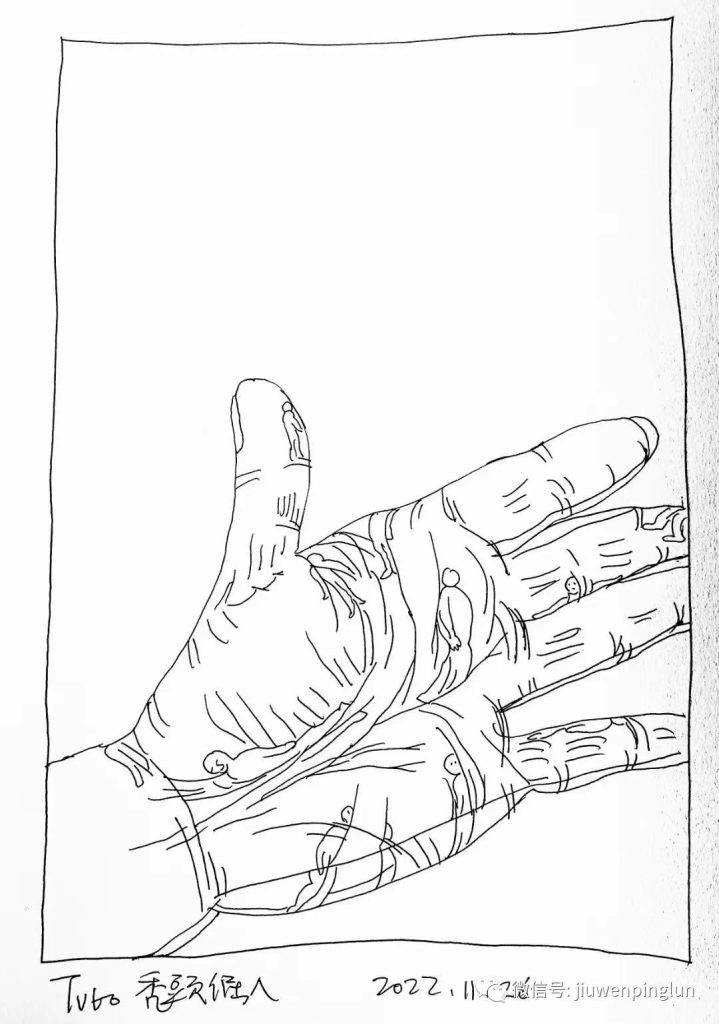

Illustration by an artist known as the “The Bald Stubborn Man,” (秃头倔人), actual name Li Xiaoqiang (李晓强).

Photo taken from WeChat

The deadly fire in the Jixiangyuan complex in Xinjiang’s Urumqi on November 24, 2022, and the online turmoil it generated it can be considered in combination. Together, these events indicate that the stranglehold imposed on society by three years of COVID-19 controls had reached its limit, as even those who supported the epidemic policies began to mutter that there was something wrong. And more and more people realized that things needed to be made right.

The official press conference on the fire turned into a catastrophe. It once again eloquently demonstrated that a press conference designed neither to reveal the truth nor to demonstrate accountability, no matter how high-minded it sounds, will be ignored by the public. Instead it generated public denunciation. Multiple press conferences going off the rails in this manner stripped this regulatory regime from any legitimacy it might once have had.

As they read their remarks aloud in as perfunctory a voice as possible in order merely to complete the prescribed task, it became more and more difficult for the officials involved. They had been selected to placate public opinion, and both they and the public knew how meaningless the press conference actually was. The reason why they sat there was because of their bureaucratic positions, not because they wanted to take responsibility, which stripped the event of any meaning it might have had.

The form, effectiveness and people’s assessment of the press conference very intuitively demonstrated the state of the dialogue between the government and the people. The officials gave their prepared remarks at the prescribed pace, took no questions, and then were unable to address the collective emotions of those present. Most local authorities are accustomed to replacing dialogue with instructions, pretending to be powerful, even while hoping to use their status as mere executors of orders to earn some level of empathy. But this kind of technique for controlling people is losing its effectiveness.

During and after Urumqi, there was a wave of people trying to educate themselves learning about the law and how to use it. More and more people, business owners in particular, studied epidemic-prevention laws and regulations, the “nine prohibitions” [stricter anti-epidemic measures announced in July 2022], “20 articles” [new less stringent rules announced on November 11, 2022 in response to growing public anger], etc., and used these to try to create a “firewall” between individuals and the government, and between families or communities collectively and the broader Chinese authorities. Under the guidance of this new knowledge, smaller-scale disputes began to frequently appear over where to draw the line when it came to epidemic-prevention policies.

After the “20 articles” were released, the official and popular attitudes toward it were different. The short-lived confusion among officials showed that they were digesting the possibly socially beneficial side of this new world, trying to understand it by first putting the new measures in a subsidiary position to the “nine prohibitions.” The general public, on the other hand, did the opposite, taking the new standards as superseding the previous policies.

The public understanding was that the basis for the previous large-scale nucleic-acid testing [which all Chinese were required to undergo very frequently, a requirement that benefited some private companies] was the basis of the existing prevention and control model. Trying to connect the testing requirements to the “epidemic” and epidemic policy was previously considered to be a conspiracy theory, but now mandatory testing was being criticized by more and more people who had come to accept this view because of the scandals that were emerging. There will always be those who benefit from the status quo and so will seek its continuation, and indeed there were those acting this way now.

No matter how an official spokesperson described the Jixiangyuan fire, whether it was the victims’ “weak ability to save themselves” or other rhetoric, it could not stop society’s questions from flooding out. Perhaps some people in authority had made a quiet calculation and decided that just over 100 days was the maximum tolerable limit, and then evaluated how various measures could be taken to mollify the public given this. If so, they misunderstood public opinion over Urumqi.

Considering that the middle class nationwide began to freely walk out of their apartment buildings and to directly spread what the law said about those still sealed in, and began to respond to and support each other across the land to test the legitimacy of continuing the policy of imprisoning people within their homes, the real problem generated by the fire in Urumqi emerged. The real question was, since we have cooperated with prevention and control for so long, and given it our obedience and loyalty, why can we still not be protected?

This fundamental question then led to individual cases of people’s interrogation of particular local prevention and control personnel, and news about these activities spread all over social media. It was impossible for people in the epidemic-control system to pretend not to see it. Every time these individual cases appeared, they received boundless applause and encouragement. And more people joined a growing consensus that they needed to know the specific identity of the specific executors of the epidemic-prevention measures, and to demand they come out of their white uniforms and answer questions.

What society hoped for in one sense is not much. It just wanted to confront specific people, not a symbol claiming to be the spokesperson for the system pushed out by that system to face the crowd. But from another point of view, such demands are quite consequential. Whether it was the Urumqi post-fire press conference or the implementation of the epidemic-prevention model, those implementing policy had been stripping themselves of all their individuality, trying their best to be part of the system, and in an unfocused manner doing things in a way that brought them as little cost as possible.

What has changed is that people no longer simply listen to orders, but hope to clearly record who gave orders, what documents the commands are based on, what measures are being implemented, whether these identification measures are legal…In other words, the public quickly completed their psychological reconstruction, discarded the subordinate role of passive acceptance, and began asking a pointed question to each epidemic-prevention person: are you really who you claim to be?

After the Urumqi fire, the ups and downs of public opinion were connected with an undeniable change in public psychology, that people now wanted to be liberated from arbitrary epidemic rules. People should defend human lives, defend the implied beliefs behind the values that society should have. In the three years since the epidemic exploded, people bowed down in the face of the unpredictable chaos it brought to their lives, until a fire reminded the people of what they should not forget.

In short, the intensity of social doubt raised after the fire in Urumqi exceeded that generated by similar accidents before. Overnight, the psychological map of epidemic prevention was now blanketed by a great deal of reflection and examination. Thankfully, people haven’t stopped talking about the law, and they feel strongly that trusting the way the government handled the epidemic led to them being trapped as they had been, and this should not have happened.