BY LIANCHAO HAN AND BRADLEY A. THAYER

As the United States and other countries begin to enjoy a break from the pandemic, China is engaging in a chaotic campaign to control its latest wave of COVID-19, with many cities locked down. This poses a serious challenge to Beijing’s zero-COVID policy — and perhaps the political future of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Since January, the omicron variant has been raging in China, causing the largest surge of COVID-19 infections since the outbreak of the pandemic in Wuhan more than two years ago. The Chinese government has ordered more than two-thirds of the provinces to initiate lockdowns, turning major industrial cities such as Xi’an, Shenyang, Shenzhen and Shanghai into ghost towns and disrupting tens of millions of lives.

Many tragic stories have surfaced from this pandemic prevention model of Chinese socialist characteristics — rigid, violent and inhumane. Some residents with life-threatening diseases or a need for treatments such as kidney dialysis are confined at home and reportedly denied access to medical care. Even some health care workers are not able to get proper care. A nurse who suffered an asthma attack went to the hospital where she worked but was denied treatment because of pandemic prevention protocols; she died.

On Chinese social media platforms, her fellow nurses at Eastern Hospital complained that they have assumed tremendous pressure to collect samples for COVID testing. In a leaked video, one nurse emotionally cries out that their work has intensified tremendously — on duty day and night, nonstop. “Everyone is already at the breaking point of nerves,” she says. The hospital has sealed doors and windows with wooden boards.

Li Chengpeng, a prominent Chinese writer, writes that lockdown horror stories will be recorded in the history books sooner or later. He cites a 4-year-old girl with acute laryngopharynx in Changchun who died awaiting medical treatment because she had no proof of a COVID test. In a residential neighborhood in Shanghai’s Xuhui District, Li writes, a patient with advanced rectal cancer could not get his radiotherapy for seven days. When he experienced internal bleeding, his wife knelt in front of the neighborhood committee and pleaded, “Please save my husband,” but the committee refused to let him leave for treatment and he died the next day. According to Li, common scenes are law enforcement officers dragging someone in front of a crowd and beating them for violating pandemic prevention rules, or train control officers sternly scolding passengers for taking off their masks to eat.

China’s zero-COVID policy includes new measures for “on-spot testing and quarantine,” which means whenever a case is found, the building where the person lives is locked down and all in the vicinity are to be tested and isolated. In Shanghai, a woman who cleans a public restroom in a residential complex spent four nights sleeping in the restroom to ensure that it was kept clean. A story leaked on Chinese social media reported that an elderly woman in Shanghai, whose travel code was out-of-date, used a public restroom and caused a group of people to be confined in it for hours. Similarly, office and factory workers have stayed overnight at company offices and factories. In some places, shopkeepers and customers were sealed off in shopping malls overnight. Mothers are separated from babies in isolation, and in one ward for infants and children there were only 10 nurses to care for 200 babies.

Two mayors in northeastern China were dismissed for failing to control infections in their cities. Even a court in Shanghai’s Jing’an District reportedly was suddenly locked down, forcing plaintiffs, defendants, witnesses, lawyers and judges to spend the night together in a courtroom.

The lockdowns and mandatory testing have made ordinary citizens’ lives even harder. As happened in December and January, Some people reportedly are starving as lockdowns have caused food to become expensive and scarce. Some have chosen suicide to end their misery. A residential community in Shanghai’s Minhang District has been locked down since March 14, and a cancer patient who was not allowed to go out to get his medicine jumped off the roof of his building. His suicide photos went viral on Chinese social media, but the government claimed the incident was faked and soon launched a counter-campaign against the negative news. Hong Kong also has implemented Beijing’s zero-tolerance COVID policy, and its suicide rate reportedly has hit “crisis level” during the current surge.

Many new cases of COVID in China have produced asymptomatic infections, leading some to question the rigid enforcement measures. Omicron has been less virulent than other variants, but it spreads easily, causing Shanghai to extend its lockdown at the end of March. Chinese government officials have said that even without symptoms, someone who is infected can spread the virus and they believe some just may not have developed symptoms yet. Still, some question why Xi has been insisting on such a strict policy.

Interestingly, Chinese observers report that on March 22, the four major Chinese news platforms flip-flopped several times between the zero-tolerance policy and a policy to “protect the economy at minimal cost,” after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Standing Committee meeting on March 17 to decide how to fight the surge. The flip-flop may indicate that Chinese Premier Li Keqiang disagrees with Xi’s policy and may have tried to exert his own power to lessen the blow to China’s economy.

It would be important to Xi to demonstrate that his policy of handling China’s outbreak is a proper prevention strategy to achieve victory over the pandemic. Any deviation, including a policy to “protect the economy at minimal cost,” could cause skepticism about his achievements before Xi gains a third term, which is set to happen later this year.

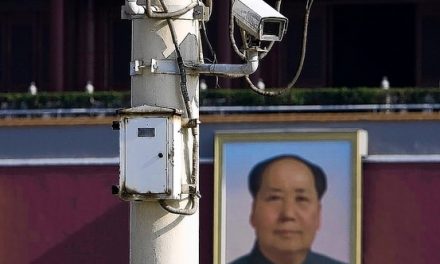

But the zero-tolerance policy appears to be unsustainable. As more residential communities are blocked off with metal barriers — some entrances reportedly even welded shut with iron bars — people are becoming increasingly unhappy about the policy. Some residents in Tandong village in Shanghai’s Pudong New District, for example, are said to have clashed with pandemic prevention enforcement personnel and broken through the blockade. All this has led to more chatter about rioting to gain eventual freedom from the CCP.

Lianchao Han is vice president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China. After the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, he was one of the founders of the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars. He worked in the U.S. Senate for 12 years, as legislative counsel and policy director for three senators.

Bradley A. Thayer is the co-author of “How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics.”

This article first appeared in The Hill on 04/04/22 12:00 PM ET