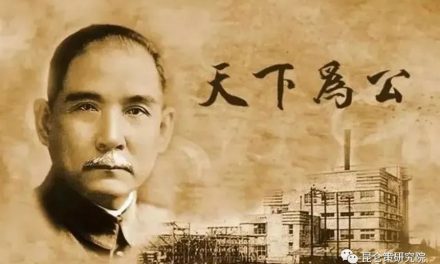

(Chinese composer Wang Xilin. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin)

WASHINGTON – According to a communiqué issued at the recent conclusion of the Sixth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Party, “since its founding in 1921 has always taken the happiness of the Chinese people and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation as its central mission, and has written the grandest epic in the thousands of years of history of the Chinese people.” However, Chinese composer Wang Xilin’s view of history is clearly different from the CCP’s. In his eyes, the introduction of communism to China and its more than seventy years of rule over the country has been nothing less than a catastrophe for the Chinese people.

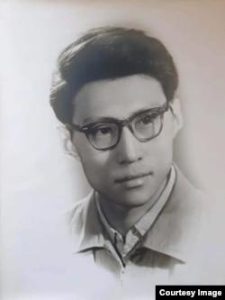

(Wang Xilin at the time of his graduation from the Shanghai Conservatory of Music in 1962. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin).

Wang Xilin is an internationally recognized Chinese composer. “Torch Festival”, the 4th movement of his symphonic suite Tone Poem of Yunnan, is one of the most frequently performed pieces by Chinese symphony orchestras both in China and abroad.

However, in the 1960s, shortly after composing the Tone Poem of Yunnan, Wang was expelled from the Beijing Central Radio Broadcasting Orchestra and the Communist Youth League. He was demoted to the Yanbei Literary and Industrial Troupe in northern Shanxi Province for his criticism of the radio station’s literary policy as empty-headed politics that reflected ignorance of art. Wang would spend 14 years in rural re-education camps before being allowed to return to Beijing as a composer in the Beijing Song and Dance Troupe.

In 1999, Wang was assigned to compose a symphony to welcome the arrival of the new millennium. In this symphony, he used the language of music to express his reflections on the world and on the past century of Chinese history, based on his own experiences.

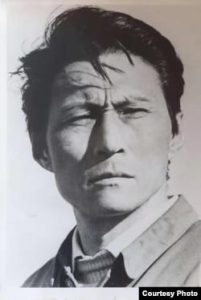

(Wang Xilin while returning to Beijing in 1978 after the Cultural Revolution. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin)

In Wang’s view, the rise of communism in China was a disaster not only for China but also for the whole world, and the abandonment of it in much of the world was the most important event of the century. This was the conviction that led Wang to write his Fourth Symphony. On the day of the symphony’s official rehearsal, the conductor asked him to say a few words to the orchestra; Wang spoke frankly, and unavoidably offended the CCP. As a result, the CCP authorities immediately ordered the concert to be canceled. His Fourth Symphony was thus banned in mainland China.

Wang, now 85, spoke about his musical experiences over the past 70 years on the eve of the CCP’s Sixth Plenary Session, which aimed to set the tone for the next century of Chinese history. His dramatically different views include that the 1840 Opium War brought industrial civilization to China and broke the thousands of years of imperial dictatorship over a mainly agricultural civilization, making a great contribution to China’s development. That was followed, however, by the CCP’s seizing power in mainland China and implementing a closed-door cultural policy, which damaged China’s cultural development and destroyed his youth.

The following is the first part of the transcript of the interview Q&A. The views expressed by Wang Xilin are his own and do not represent the Voice of America.

Why musicians can be punished for speech crimes in China

Q: As an internationally recognized Chinese composer, you have been repeatedly punished for things you said, including a 14-year exile and a long ban on your works such as the Fourth Symphony. Suppose someone asked you, as a composer, why don’t you use music as an implicit form to hide your thoughts and feelings instead of making sensitive issues explicit, thus causing damage to your career? How would you respond?

Wang: The story of the creation of the Symphony No. 4 is an interesting one. In 1999, a year before the turn of the millennium, cultural organizations of all kinds were preparing for the event by creating large-scale works. Beijing TV, one of the Beijing Municipal Government Agencies, invited several writers to throw light on the past century, mainly in celebration of it. Some composers, including me, were among those assigned to do such work for the Beijing Music Station.

While accepting the assignment, I thought I couldn’t write the way they expected, so I discussed it with (musician) Zhu Jianer, who also received the assignment. We decided to ask if it would be possible for us to write untitled works. It was a good idea, no titles. So we asked the Beijing Music Station if we could write such works, which they agreed to.

That seemed great! We thought that would give us a lot of creative freedom, and enable us to think and write outside the box. But, in fact, they asked us to write dedications, for example, to the motherland for the millennium, and so on. The idea of writing a dedication was very confusing to me. How should I write the dedication? I didn’t want to write the dedication the officials wanted, because I had another dedication in mind, based on my long-held view of 20th-century human history.

(Photographs taken in May 1962 showing refugees fleeing the Great Famine in China lining up for food in Hong Kong.)

I believe that the history of humanity in the 20th century is mainly the history of communism from its rise to its fall, which was that century’s biggest event. I let this idea govern this work, so the first piece of it was a journey of suffering, and the music here is very sad and deep. The music is very much targeted, yet at the same time general; that is, I applied the music of local opera and enhanced it with symphonic thinking, to write about the conception of the Chinese nation and its journey, making the job very meaningful to me.

After the Fourth Symphony was done, I felt quite satisfied with it. The symphony itself is untitled, which means there are no words to explain, and I never use words to explain my music. On the day of the official performance rehearsal, the orchestra called on me to show up. The conductor asked me to say a few words when the 70- to 80 – person orchestra was ready to rehearse. I said to them that the 20th century had been marked by many events, including two man-made world wars that killed countless people, and great advances in science and technology, but in my mind, the greatest event in the history of human development was the eventual abandonment of communism, which mankind had pursued so fervently.

(People climbing the Berlin Wall at the Brandenburg Gate after the opening of the East German border on Nov. 9, 1989. Reuters/Herbert Knosowski)

Everyone applauded when I finished speaking. But that one sentence revealed my inner thoughts. Someone reported me to the authorities, and the concert was canceled. A few days later, the Cultural Bureau asked me to attend a meeting. In it, a Bureau official pounded on the table and said to me, “Mr. Wang, your speech has violated the ‘Four Basic Principles’, so your concert has been canceled.” I asked exactly which words of mine had violated these principles, but he would not say anything more. I thought to myself that it must have been the sentence I mentioned, and that it had been decided to remain silent, not a word to be spoken or written down in response.

What is the content of the Fourth Symphony?

Q: In China, neither you nor the researchers of your works can publicly discuss your Symphony No. 4 in detail. Can you now tell us about its specific content?

A: As I said, I believe that the history of humanity in the 20th century is substantially the history of communism from its rise to its fall, which is the century’s most significant event. This belief is the guiding principle in composing my work. So its first piece is a journey of suffering, and the music is very deep and sad. This journey has great relevance, as I applied local opera music to write about the conception of the Chinese nation, the journey of the nation. I used Qinqiang, or music of the historical Qin area, one of the oldest theatrical genres in traditional Chinese opera, as well as the Pu opera, from the middle portions of the Yellow River. Both are distinctively Chinese genres of music. (Piano demo)

I was very dedicated to this theme. I applied the music of the central Yellow River region to make a symphonic theme out of the Qinqiang and Pu opera to express the suffering souls and tragic fate of the Chinese nation, like the enduring agony of a prisoner in solitary confinement.

(A camel caravan in the desert of Gansu, China. File photo)

The theme of imprisonment appears several times in my works. The first time was in the Third Symphony, which differed from the Fourth in that it was written entirely based on Western languages. In 1999, when I began writing the Fourth Symphony, I was contemplating the fate of the Chinese nation which, for me, was like the fate of prisoners who were suffering in isolation. We cannot see their faces, writhing as they move forward like a gray herd of animals on a vast snowy plain, coming from nowhere and heading nowhere.

In my opinion, the fate of the Chinese nation was like the fate of such prisoners, hands bound without freedom. This is the basic idea of the work, the fate of these prisoners, the fate of communist-ruled China, which is something I was not permitted to say in words. I put this idea into the language of music, and I think it worked well. This theme has a high artistic value. It uses the techniques typical of Western works but is laden with Qinqiang and Pu opera as well as the techniques of Bach. That’s why Western musicians, when listening to it, can perceive a unique, tragic language in the Wang Xilin style, and they speak quite highly of it.

The second movement of the Fourth Symphony takes a very different turn. The first movement is nearly ten minutes long, with a five-part fugue for strings, which expresses the theme of endless suffering. I especially like this theme, which expresses my overview of the fate of the Chinese nation. What theme can you find in the second movement? A kind of image of a violent storm, that’s the vision I bestowed upon it, to show the brutal history of communism in China. How to do this? I thought of torture inside the walls of a prison. What is the most terrible torture? I thought about it for a long time, and finally thought of the horrible creaking and smoking sound of burning red iron on the human body.

I wanted to find the sound that shows this greatest pain, but where to find it? I listened to Alfred Schnittke’s Symphony No. 5, which I heard during my visit to the United States in 1994. I searched for other examples too, but I couldn’t find many, so I borrowed materials from friends in various countries. A foreign friend helped me find the full score of Schnittke’s symphonies. I transformed this sound and a few others that I had found into my own soundtrack of a great catastrophe.

So how to express this sound? I used the highest notes of the violin, the highest notes of the strings, three piccolos, and three clarinets in E-flat and B-flat. To these highest tone in an orchestra, I added the lowest tones, using the trombone and tuba. In the middle, the percussion instruments were added, and the xylophone was used. This immediately evokes the image of the red iron on the human body.

On top of this, there is the sound of gongs and drums, which are used to indicate a disaster in Peking Opera. An important form of percussion to evoke tragedy in Peking Opera is the “chaotic hammer,” the beating of the gong and drum. These gong and drumbeats are often applied when a battle is lost. The beats very much resemble our folk image of suffering and hardship. This is the second movement.

Expressing the Chinese people’s sufferings, tears, and hope through music

(Photo of Wang Xilin at work in 1998. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin)

The third movement of Symphony No. 4 is my musical expression of crying. There are various kinds of crying, and I wanted to evoke a kind of ghost weeping. I thought of many ways to express the crying of ghosts, as there are many ghost plays in works in Peking Opera and other regional opera forms. We must not underestimate the power of expression in such ghost plays, in which people are wronged, and so a ghost goes before the king of hell to plead. In Peking opera or Hebei opera, there is a terrifying king of ghosts, Zhong Kui, with extremely intimidating make-up. Zhong Kui is sympathetic to the people suffering, making ghost plays deeply rooted in the hearts of the Chinese people.

Chinese ghosts are different from ghosts in the Western theater, as in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The ghosts in Chinese ghost plays are all sympathetic to suffering people, as in Sightseeing on the West Lake and Three Drops of Blood of the Qinqiang, as well as in many other ghost plays. I studied many ghost plays in order to learn about the sound of ghosts crying. How to express the sound of ghosts crying? I looked into the Polish avant-garde music of [Krzysztof] Penderecki to find this language, using violin trills and overtones to express a flickering aura, and using this background of crying to set off all kinds of sounds of crying. (Piano demo)

This tune derives from the Qinqiang. By organizing the music in a symphonic way, it becomes an old man moaning at history against a background of weeping. Here you hear both weeping and sighing sounds, but that’s not all. In the “sighing soprano” portion, the soprano of the first and second violins are added to the weeping sound, and the weeping of one person develops into the weeping of a group of people, and the weeping becomes louder and louder, building to a crescendo that comes to represent the grievances of the whole nation. This is the third movement.

The fourth movement of Symphony No. 4 is about hope. What is it about, given that I can’t promise false hope in my music? The commonplace and cheap delusional expectation found in many works is nothing but deception. What I have sought and searched for a long time is how to deliver the message that there is still hope for humanity. One day, walking on the street, I saw a group of children being led across the street by their babysitting aunt, and all of a sudden I got this idea: Ah! Life! Life is something that no tyrant can cut off. So I decided to dedicate the closing portion to the fire of life, to demonstrate where the breath of life comes from.

That’s what I wrote in the fourth movement. At the same time, I knew that whether there is hope or not, mankind still has to struggle to find it. So I emphasized this idea in the fourth movement. In the deep-bass background, a single weak horn sound appears in the distance, which then gradually increases to four horns to slowly express the theme of a prolonged, tedious journey. This sound of hope gradually builds up until it is suddenly interrupted by the tragic theme of the adagio from the beginning of the first movement, spliced in here. In this way, the fourth movement concludes.

Exploring new ways of music composition to express thoughts and feelings

Q: You are one of the most important Chinese symphony composers on the domestic Chinese music scene. In your Symphony No. 4, you used a lot of sound-collage and sound-mass techniques, and your use of orchestration, pitch, and rhythm are distinct from that of other Chinese composers. You said that this symphony is dedicated to “the past and the future centuries of Chinese and human history.” Can you tell us why you think the application of these musical techniques is necessary for the ideas and emotions you intend to express?

A: That’s a very good question, and I think it deserves mention. Yes, I put a lot of effort into finding these techniques of expression. I have three sources for my music. The first is my soul as a composer; the second is technology from the West, that is, the structure of the symphony, the fundamental ideas, all Western; the third, traditional Chinese music, including local opera. These three factors can be considered the generalization of my own creative thinking. And such a general outline as a whole is the mission of a composer. For example, I want to express the tragedy of the nation’s destiny through music. In the first movement of my Symphony No. 4, I used the first part of the slow movement, and I wrote a long portion, approximately ten minutes, I think. The second movement is about catastrophe, and I considered so many ways to do this.

In the second movement, reflecting on catastrophe, I got the feeling that my fate was like that portrayed in Dante’s Divine Comedy. In the second part of the Divine Comedy is a painting of a pair of lovers variously flying and floating in the air, over a miserable gloomy wind. This scene made me think of the fate of China — my own fate, and the fate of my country, my nation. Speaking of my fate, it was like being in a big dark, unfathomable pond. I was floating in this dark pond of water, up and down, unable to see the sky. That was my fate in the Cultural Revolution.

I wanted to show this dark pond, which is the central part of my fourth symphony, the catastrophe part, with the rhythm suggestive of whipping. I searched all kinds of materials for this disaster imagery. This is a way to show the torture our people have suffered. I wanted to create a kind of sound for such imagery. How to do this? I borrowed the 20th-century sound-mass technique from foreign countries.

First of all, the sound-mass technique came from Poland, a nation that suffered a lot. The Polish avant-garde is particularly influential in Eastern European countries, as you can find in Krzysztof Penderecki and Witold Lutosławski.

(Chinese composer Wang Xilin chatting with Polish avant-garde composer Krzysztof Penderecki in 2012. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin)

Using music to depict the scenes and feelings of calamity

These two composers were the main subjects of my research when I was immersed in the study of the Polish avant-garde. One of Penderecki’s works, Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 string instruments, applies electronic music to express this terrible catastrophe for humanity. I only heard it when I returned to Beijing in 1978. I was already 42 years old at that time, and then I began to study modern techniques before starting to write my Third Symphony in 1988. I began to write scenes of great suffering, of grand destruction, of outbreaks of war and scenes of the tragic death of humankind, as I learned about the devastated lives of the so-called “Hu Feng Group” as well as the tragic fate of the rightists.

I had to find the technique to express such scenes, and after digging for a long time among Western musical works, the Polish school became the major source. To learn the technique of the Polish school, I had to first absorb it thoroughly, and then I had to alter it. In the Polish school, there is no such weeping sound as found in my work. I used high-pitched tones, portamentos, and overtones on the violin to evoke shimmering tears, and to depict such a scene as found in the ancient poem by Du Fu,

“Have you not seen,

On borders green,

Bleached bones since olden days unburied on the plain?

The old ghosts weep and cry,

While the new ghosts complain;

The air is loud with screeches and screams in the gloomy rain.”

History repeated itself for the 30-40 million ghosts who died in the “Great Famine” in China after the “Great Leap Forward.” I divided the violins into a dozen voices, layer by layer, evoking the falling of tears or the bones of the dead.

For example, in my Fifth Symphony, I use these sounds to express moaning in dreams or in reality. An urge to cry, but no more tears to shed, that is, the sobbing after crying, until you lack the strength to even sob. What I want to show is the cruelty political persecution is. It forces you to confess the “crimes” of your thoughts. I had been criticized and denounced, as were many, many other people, including old comrades in the CCP, some of who were tortured to death. I have witnessed extremely brutal scenes and heard stories of tortured people in distress in prison at night. Some people were simply driven crazy! I myself was in a psychiatric hospital for six months, and I had nightmares in which I was afraid to see the color red, or to see the image of the “supreme leader.”

How does this feeling of schizophrenia manifest itself? I turned this feeling into sound masses. At the beginning of my Fifth Symphony, there is this monophony that grows into 12 sound masses. This application of sound masses in performance has been very much admired and thought to be a valuable creation. This technique was completely original. Here I wanted to express my inner feelings — for example, this is how I felt when I was struggling and nearly driven mad, or when I was put in jail and unable to cry out.

This is how I learned to borrow Western techniques. The first thing for each one was to absorb it thoroughly, digest it completely, and then translate it into my own language and express my own feelings after learning it.

(File photo: Big-character posters and slogans of the Cultural Revolution at Qianmen, Beijing. (January 26, 1967)

This kind of feeling is not found in the West. Those who write a sound mass there have not necessarily been in prison or wept in the darkness of a prison nightmare. Political persecution is a terrible thing, and there is a book by Mr. Shao Yanxiang that mentions the so-called “being buried beneath the waves,” the calamity of being drowned, a quote from the words of Mao Zedong. Mao once called people to “fight the enemy, plunge the enemy into the ocean of people’s war, let them be buried beneath the waves.” The same goes for those of us who are criticized and denounced. And the slogans of “Down with” and “Smash” were also so deafening during the Cultural Revolution.

This is what I wanted to write about: people while being drowned fighting to grasp a straw. So I used this kind of sound mass to show extreme distress, which makes me cry when I think about it. This is where my own creativity comes from, where my originality comes from. This creative language is the result of my study of Western techniques. There are some other instances, for example, at the end of the Fourth Symphony, the third movement needs a sublimation after the expression of shedding the bitter tears. So I use the first violin and the second violin, and this kind of sound mass is used to represent the crying of an individual suddenly transforming into that of a large crowd.

How can a composer be considered creative?

(Composer Wang Xilin draws inspiration from the mountains, rivers and trees. Photo courtesy of Wang Xilin)

Even in my Yanko Dance of Taigu, a piece depicting folk-celebration dance, I wrote a movement called “Funeral Song.” There are plenty of people who suffer in the countryside! When I wrote the “Funeral Song,” I used a bassoon solo to convey feelings of sorrow. This styling comes from local opera, and I combined it with the foreign-language 12-tone music to form my own language of weeping and suffering. My music is full of such language, but previously no one ventured to study this work. Now that it has been studied, I still dare not say what my music is about. The Fifth Symphony was performed at the Elbe Concert Hall in Hamburg (Elbphilharmonie), Germany, in May 2021, and you can see the video of the performance, conducted by Johannes Kalitzke. Of course, it’s also about anger and the pain that comes out of that anger.

I think that’s the only way a composer can be considered creative. But we don’t see such creativity in our conservatories now because people are too far away from and too afraid of reality to get in touch with it. What is the point of education when everyone despite being educated speaks falsehoods and empty words, both common practices since ancient times? It is meaningless. Only works that bear your own witness and express your own views on history, and on the nation, have meaning.

That’s what I do. My works express my own views after studying Western techniques and combining them with local Chinese opera. But I can’t say this in public; I’d be casting myself into a net. The authorities are now strangling the arts so much that the latter have no future.

Therefore I am very pessimistic about music education in China, which is destroying students, generation after generation. Such a great sin. This is what I have observed.

Personally, I have strongly criticized the Chinese Communist Party’s closed-door cultural policy. I feel that I had been sacrificed during my youth, even 14 years before I was formally persecuted. I was not allowed to return to Beijing until 1978, after the Cultural Revolution, after Mao died. I was already 42 years old at that time! Only then was it possible for me to hear Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, to study Schönberg’s twelve-tone system and Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.

Forty years have passed since the Cultural Revolution ended, but the reflections on and criticisms of it are still far from enough. In the film industry, there are at least a few films that accomplish this, such as Farewell My Concubine and Alive. But in the music industry, there are simply no comparable works.

(Translated by Heather Liu and Evan Osborne)