By Huang Yicheng Nov 2, 2023

Editor’s note: Huang Yicheng participated in the white-paper demonstrations in Shanghai in 2022. He managed to flee the country, and studies in Germany now,

The several nights of 2023 Halloween-associated parades in Shanghai [in which people dressed up in costumes and walked through the streets on and just before Halloween in 2023], with thousands of participants constituted the largest social movement in Shanghai since the white-paper movement centered on Urumqi Middle Road in 2022. From October 28th to 31st, for four consecutive days, citizens gathered in the southwest area of the intersection of the Yan’an East and the North-South elevated roads (the center of Shanghai), mainly on Julu Road, Changle Road, Huaihai Middle Road, and Chengdu South Road. These are about a ten-minute walk from Urumqi Middle Road, were once part of the Shanghai French colonial concession, and now constitute a high-end area densely populated by foreigners. During the four consecutive days of this social movement, the atmosphere was very relaxed, and no one was arrested. On the evening of November 1 (Wednesday), the Shanghai police did deploy a large number of police forces to surround the area, but after that evening no further protest participants appeared.

The 2022 demonstrations in Shanghai were part of the nationwide white- paper movement, and Shanghai’s demands during that time were the most radical nationwide. Many demonstrators were arrested, leaving behind a legacy of huge psychological trauma for many participants. Therefore, this time when the police surrounded participants on Yan’an East Road and the North-South Viaduct on the night of October 31 (Tuesday), many said that for them it triggered a great sense of anxiety and fear. But because there were so many participants, the police diverted the crowd southward, possibly fearing a stampede, and it became a spontaneous carnival-style parade. Compared with other activities commemorating the death of Li Keqiang in other parts of China during the same period, the social movement in Shanghai took on a unique vocabulary and style of expression, demonstrating the uniqueness of Shanghai itself.

The original idea of a decentralized or leaderless social movement mainly came from Hong Kong in 2019, but Hong Kong already had a relatively mature civil society at that time. Although there was no large organizing platform, there were still many small social groups mobilizing. In contrast, civil society in the mainland is very barren, so the degree of decentralization of necessity had to be even higher than in Hong Kong. And so the 2023 Halloween parade was more decentralized than the 2022 Wuzhong Road rally. This model for social movements protects the safety of activists to a certain extent, as it makes it more difficult for the government, and police in particular, to monitor. The entire event was unorganized, as scattered members of society gathered together spontaneously. Most participants did not have clear political demands, and a small number of activists used metaphors to allude to current ills. Examples included women dressed as male genitalia, “Winnie the Pooh” suits (alluding to Xi Jinping), and carrying signs saying “Down with Cheng Die” [a character in the Zhang Yimou film “Farewell, My Concubine” who is denounced during the Cultural Revolution]. The bravest thing was someone who covered his or her body with and held up white papers, representing the epidemic-prevention personnel who had used huge cotton swabs when conducting their nucleic-acid tests. We all know that doing such things in mainland China carries huge risks. But each activist brought his or her own creative flair to the scene, turning the night streets of Shanghai into a mobile feast. Ordinary citizens spontaneously constructed their own vocabulary as they constructed a social movement, and a parallel culture emerged that confronted official discourse.

This parallel culture is a concept proposed by social activists such as Czechoslovakia’s Václav Havel in 1968. They believe that social movements need to construct such a culture that is different from that associated with official discourse. This parallel culture slowly grows like weeds, gradually replacing the latter’s hegemony. This process is often long. In fact, in the 1960s, in addition to social movements such as the Prague Spring in the socialist camp, social movements in the capitalist camp also soared: there was Woodstock in the United States, the Yasuda Lecture Hall Incident in Japan [in which a building at Tokyo University was occupied for several days], the May 1968 upheaval in France, etc. These social movements have had a huge cultural impact. For example, the basic paradigms of rock and pop music were born in American society in the 1960s, and Bob Dylan, a representative figure if the associated movement, was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In the words of a French cultural theorist, all cultural forms are the condensation generated by social movements.

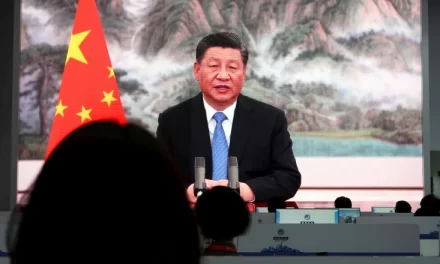

At present, China’s domestic cultural hegemony is strictly enforced by the government, which emphasizes a kind of lunatic xenophobia, nationalism and patriarchy. In fact, such nationalism and patriarchy are different reflections of the same phenomenon. Xi Jinping is the core symbol of Chinese patriarchy. His leadership is an absolute taboo subject in current Chinese society and culture, and no one is allowed to touch it. All argot conventionally used to refer to him has become banned as “sensitive” words. Years ago, I visited Tiananmen Square with an Italian friend. This friend asked me if he would be arrested if he walked down Chang’an Avenue wearing a T-shirt with Winnie the Pooh on it. My answer was definitely yes. This kind of hypersensitivity and belief in taboos casts a huge shadow and sense of depression over Chinese society’s psychology. It relies on a typical sense of mystery or awe to suppress and control society. Therefore, social movements must first challenge this patriarchal symbolic order. Seen this way, the white-paper movement as seen on Wuzhong Road, the Halloween Parade, and the feminist movement, the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer movement (LGBTQ) are all at the forefront of China’s social movements. This is by no means an accident. In social movements in Hong Kong, this feature is not as obvious as in the mainland. But this is because the social culture on the mainland is more repressed than in Hong Kong.

In the Shanghai Halloween parades, we saw many LGBTQ elements. For example, a woman dressed herself up as a penis, and was eventually taken away by the police. Such performance art mocks the current prevailing “phallocentrism” in contemporary Chinese social culture. The Chinese government’s rule over society relies on both violence and people’s fear of the corresponding violent machinery. This top-down violence and bottom-up fear together constitute the center of this symbolic order, this patriarchy, symbolized in turn by the phallus. The giant portraits of Xi Jinping that dot the streets of China are also metaphorical forms of this phallic symbol. The challenge to the symbolic order is equivalent to challenging this violent machine. I remember that on November 26 last year, the activists who led slogans on Wuzhong Road and shouted “Xi Jinping step down!” and “Communist Party step down!” also shouted criticisms of “patriarchy,” but unfortunately very few then responded. And there has never been a clear line between performance art and social movements. Others costumes this time, such as Yu Ji, the role played by Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung), and many others that blur gender boundaries could also be seen as challenges to society’s gender order.

It is difficult for the authorities to directly ban such a large-scale spontaneous social movement, so they instead attempt to co-opt it. Some recorded images with clear political connotations (such as “Becoming Cheng Dieyi”) were banned, but other images were allowed to be disseminated on the domestic Internet to a certain extent. This is in contrast to the Chinese official’s strict prohibition on people mentioning the white-paper movement online. Even the semi-official commentator Hu Xijin expressed support for the Shanghai Halloween parades. But the narrative method he adopted was intended to assimilate spontaneous social movements into official discourse. This was their usual “pit one faction against another” approach. However, the Chinese government’s way of governing has always been to suppress and dismantle spontaneous civilian organizations. When the people inexplicably very quickly organized themselves in the name of a Western holiday, it is conceivable that the authorities were afraid. Chinese officials have used stigmatizing propaganda to deal with Hong Kong’s movement against the extradition law and banned and silenced the white-paper movement, but adopted a co-option approach to the Halloween parade. Their propaganda and narrative strategies are clear. However, as long as the people have the ability to self-organize, they will always make “disharmonious noises” as they confront and challenge official discourse. In the future, thus, official discourse will continue to engage in a back-and-forth offensive and defensive battle with private civil society. Compared with Hong Kong society, which is now spent, social movements in mainland China such as seen in Shanghai are still in their infancy, and there is still a lot of social energy that has yet to be released. It is foreseeable that the 2023 Shanghai Halloween Parade will be recorded in the history of Shanghai and Chinese social movements. And in the future, young people will inevitably develop more diversified and creative tactics as they practice leaderless resistance.

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247639&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.