By Hu Ping

Editor’s note: Hu Ping was sent down during the Cultural Revolution, and attended the reopened Beijing University before becoming involved in local politics. He came to the US to study, and has since been an important figure in the exile human-rights community, serving among other things as the editor of the magazine Beijing Spring. Here he makes the pragmatic argument for nonviolent resistance to the CCP dictatorship, in support of a new campaign to promote such.

This call for essays on a “Non-Violent Non-Cooperation Action Plan” is very important. Here, I would like to share two thoughts.

1. Why nonviolent?

We advocate nonviolent resistance not only because it is more in line with our moral principles, but also because it is realistic, and feasible. A Hunan farmers’ rights leader named Ni Ming has said, “The reason why farmers are not turning to violent resistance is not because they lack the ideological foundation and emotional preparation to do so, but because the era of swords and spears has passed. Merely raising a pole cannot create a flag to rally around, and merely chopping down a tree doesn’t make you a soldier.” Ni Ming said that with the sharp conflicts between the government and the people in China today, if swords and spears had been useful, violent protests among the people would have happened countless times. Adam Michnik, an adviser to the Polish Solidarity Union, made it very clear when answering a question from a Western reporter about why Solidarity adopted non-violence rather than violence: “We don’t have guns.”

The CCP has cutting-edge military and police forces. As Liu Xiaobo, who had experience on the front line of protests, said, “In the face of violence, you can’t fight, but can only teach people using words.” It is true that Liu, who advocated nonviolent resistance, failed, but he carried out such resistance again and again; while Wang Bingzhang [a Chinese dissident abducted in Vietnam in 2002 and imprisoned since] and Peng Ming [a dissident who had escaped to the U.S. before being kidnapped in Burma in 2005 and then incarcerated, dying in prison in China in 2005], who advocated violent resistance, never managed to carry out a violent protest. Is that a wish they were unable to carry out? Was it because they don’t have the courage to put it into practice? No. It was because they didn’t have the tools, the means to do it.

Many still habitually and unreflectively think that violent resistance is the ultimate choice for protesters — when all nonviolent resistance has been tried and failed, protesters have to resort to violence in the end. But what they are unwilling to face and think more deeply about is, what if violent resistance also fails? Or what if there are no violent tools or methods that can be used? What then? Doesn’t this mean surrender, giving up, obeying?

This is why we insist on non-violent struggle. Because we know that we have no guns and cannot engage in violent resistance, yet we are not willing to give in. We still had to fight, so we rediscovered nonviolent resistance. Today, for us, the only realistic means of resistance is non-violence. So we must persist in non-violent struggle.

2. How to break through the difficulties of collective nonviolent action

Regarding nonviolent action programs, I previously proposed two, one called Operation Promenade and the other Operation White.

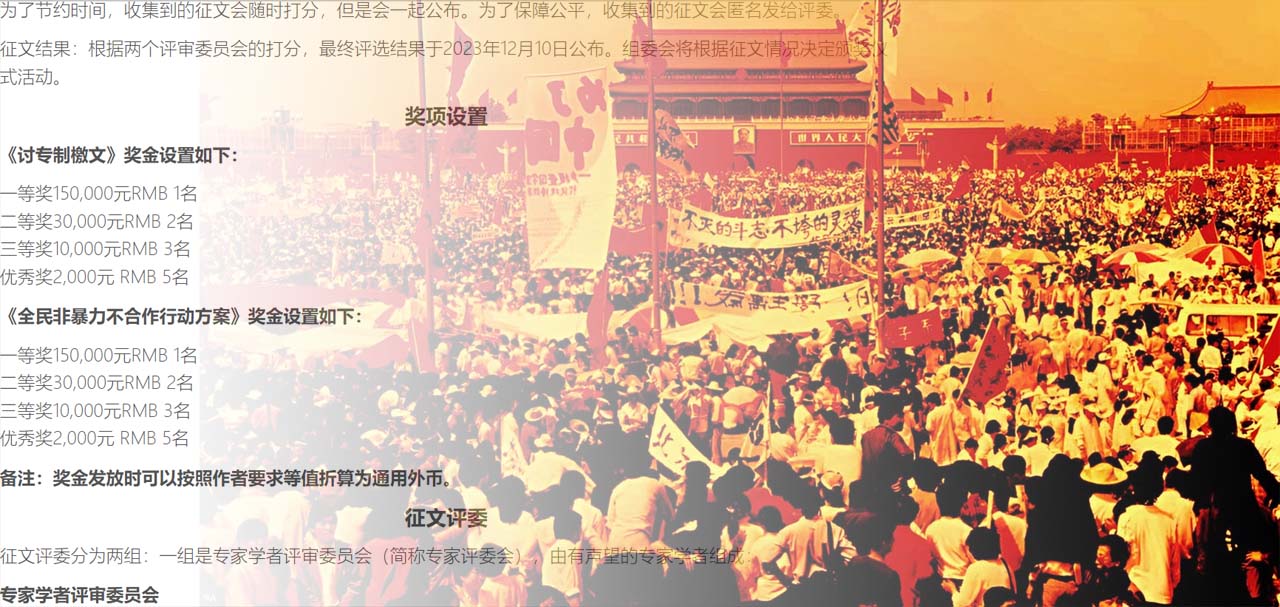

On February 10, 1990, I drafted a leaflet, “Go for a walk in Tiananmen Square.” Among the leaflet’s appeals: “In order not to forget the past and to create a future, let us reunite in Tiananmen on April 5 this year (the anniversary of the April 5th Tiananmen Movement in 1976).” “We are not going to the Tiananmen rally. We are not going to Tiananmen. I just want to go for a walk. This need not be approved, and can’t be prohibited.” “We can go alone or in groups, but we don’t want to go in a group. We don’t need to raise flags and slogans, we just need to walk naturally in the square. We can talk, we can sing and dance, we can be happy, We can be sad. We can also just be silent. As long as we look at each other and smile, the scenes merge into a whole; as long as we extend two fingers, our hearts are connected. We exchange deep emotions in silence, express clear wishes implicitly, and express all of this calmly. We will be a powerful force. As long as tens of millions of people stand in Tiananmen Square, it will become the focus of the world’s attention. All people will be able to fully understand the full implications of the calm crowd in the square.”

And the largest walking event we know of was the Jasmine Walk in 2011. Inspired by the Jasmine Revolution of the Arab Spring, on February 17 of that year an overseas website posted an anonymous article calling on the Chinese people to take walks in 13 domestic cities on Sunday that week (on February 20) to participate in the Chinese Jasmine Revolution. The article quickly spread across the Internet. On the 20th, crowds of people, including a large number of police, plainclothes officers and reporters, actually appeared at designated locations in those cities. This attracted extensive reports from overseas Chinese and Western media, thus constituting a truly historical event.

Another nonviolent action program I proposed was Operation White. On April 1, 1990, we issued a letter to compatriots across the country, “Operation White, Commemorating the National Tragedy.” On the eve of June 4th in 2009, another appeal was issued: “On June 4th, please let us all wear white clothes to express our grief and protest.” The appeal read: “June is summer, and people often wear white clothes. The authorities cannot tell who among so many people wearing white clothes are commemorating June 4th. The authorities cannot bring trouble to you just because you are wearing white clothes.” “If there are thousands or even tens of millions of people wearing white on June 4th, thus forming a sea of white, how shocking it will be! It will surely move the whole of China and even the world. It will mark the movement’s greatness, and the national spirit will be reborn from the ashes.”

It is understood that in many areas, many people wore white on June 4th. The Chinese Communist authorities themselves via their state of nervousness and strict vigilance ironically caused our plan to succeed. Taiwan’s “China Times” published a report on June 5, with the title: “Colored-shirted soldiers walked away, and the white-clothing protest made Tiananmen Square even eerier.” The report stated that on June 4, in Tiananmen Square, in addition to plainclothes soldiers and policemen, and in addition to the dense crowd, there also appeared “a large number of ‘volunteers’ wearing red, blue and green shirts, entering the event as tourists, and the atmosphere in the square seemed extremely ‘orderly’.” These colored-shirt troops “were organized in groups of about 20 people each.” “People were organized into groups, and moved to different areas of the square”; they “still stuck to their posts” even through a brief shower; their number “may be as high as several thousand or more.” “Although the square was open to the public, at the entrances on the east and west sides, public security conducted stricter inspections on every visitor, and asked them for relevant background information.” This was obviously a strategy in response to Operation White. The nervousness of the authorities was on fill display. Some Western media also reported on this.

In a society without freedom of speech or assembly, the key to creating large-scale non-violent protests is to minimize the risk of taking the first step. You go for a walk in the square and put on white clothes. It’s absolutely safe. Even if the authorities suspect you have ulterior motives, there is no action they can take against you. Unlike other forms of collective action, the characteristic of such as the walking and white-clothes actions is that they do not make participation more risky because the number of participants is too small; nor does such an action trap you, or make you feel embarrassed because only a few people participate. If there are many people participating, even if you remain silent, you can still display a kind of power. If there is a day with a large number of people participating, we can make gestures for the cameras and turn it into a public protest.

The above plan of nonviolent action has two advantages. First, it is low-risk. Second, it can advance and retreat as well as attack and defend. This may have significance for enabling us to break through the dilemma of collective non-violent action under political pressure.

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/2023/09/23/drawing-from-eve…t-plan-of-action/before the text when reposting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.