By Jianli Yang

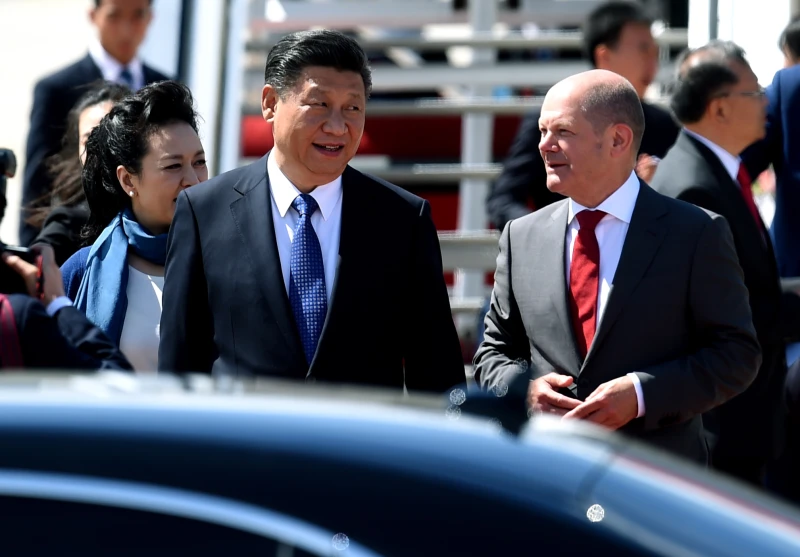

A year ago, in early November 2021, on a visit to Taiwan, a member of a European Parliament delegation claimed that Europe “stands with you” on,” reminding the world of where EU-China relations stood in light of China’s human right violations and threat to democracy in Taiwan. Such tensions have intensified over the past year, resulting in such confusion and distress as the signal Scholz sends with his visit. While Scholz initially declined French President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal to embark on a joint-visit to the country, Scholz is now the first government head from Western Europe to visit Beijing since the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent lockdowns took place.

Developments in China have been nothing short of historic over the past month for reasons that have sharped concerns about the country’s increasingly totalitarian politics, and how they portend conflict with Western democracies. The momentous 20th National Party Congress, confirmed Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third consecutive term in office as Supreme Leader of the nation. Xi badly wants world leaders, especially those from major democracies and economies, to come to Beijing, to recognize the legitimacy of his virtually monolithic leadership, and pay respect to it.

Despite China’s brutal zero-COVID policy and its disastrous effects on the country’s economy, China retained the position of Berlin’s primary trade partner. In 2021 alone, trade between the two countries cumulatively amounted to €246 billion. At the same time, the general European trend has been to pull back from economic cooperation with China. Foreign direct investment into the country from the European Union dropped by a significant 11.8% during 2020. While trade picked up slowly but surely during the first half of 2022, as can be seen by the 15% rise in EU investment, a quarter of European companies continued to debatepulling out and redirecting investments elsewhere in the midst of constant virus outbreaks in China.

China-EU relations have cooled since 2020 over Beijing’s human rights violations across the country and the persecution of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang and other ethnic minorities in particular. The EU and the western community have stood together so far in their stance against China’s overly oppressive moves to squash the rights of the people. But Germany has steadily deepened trade relations with China, in contrast to the bigger EU picture.

Over the last 10 years, Xi’s regime has taken particular measures to clamp down on the basic rights of the common man, tightening control over the lives of the people, including intensive virtual censorship as well as the swift removal of any and all “agents of chaos”, in the government’s bid to “maintain stability.” However, during Chancellor Scholz’s relatively short tenure, his government has not appeared to allow these developments to affect trade policy.

No one should minimize Germany’s dilemma; China is its main trade partner. But Sholtz and other leaders are not taking serious steps to wean German firms from dependence on the Chinese market. Another major trading partner, the Russian Federation, has, flush with German gas revenues, invaded a neighbouring country in a war that has claimed perhaps 100,000 civilian lives. Germany was repeatedly warned of dependence on Russian energy. Germany leaders ignored, and even demeaned these warnings, yet have not learned their lesson as regards trade with another, potentially even more threatening malign power, China.

The upcoming visit with the country’s top businessmen and industrialists (including the chief executives of Volkswagen, Adidas, Deutsche Bank, BMW and BASF among others) suggests anything but a protest against Beijing’s subversion of universal human rights norms, while Germany postures as a protector of universal human rights as one of the strongest members of the European Union. Germany’s current position on the political stage is starkly different from the one that the nation has played in the past. German representatives have, for the past three years, been key in holding China accountable for its abuses by shining light on the matter and condemning Beijing’s callous actions against its own people. But Germany’s words and deeds are far from consistent, resulting in frequent charges of hypocrisy and sanctimony from civil society critics.

And while their leader assures the German people of his intent to “question” and raise concerns over China’s human rights record and its trade practices (by pressing China to open its markets), it’s clear that these flimsy and ‘good Samaritan’ gestures are nothing but conciliatory ploys to distract from the more important issue that Berlin proceeds to pursue. The EU, whose China policy is largely driven by Germany, has been pushing Beijing to “respect human rights and open up markets” since 2020, demands that have not been taken seriously while the EU has been seeking a major investment agreement with China (one that was eventually dropped).

The announcement of Scholz’s trip to China occurred in the midst of a controversy about his attempts to allow a Chinese company, Cosco to invest in a terminal at Hamburg port (the biggest in Germany), which as opposed by opposition parties and his own coalition partners as well as the general population of the country. Scholz was eventually forced to accept a compromise that reduced Chinese leverage.

Since the mid-2010s, Germany has collaborated with Chinese projects with caution, and is still not a formal signatory of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Berlin has even tried to stay ahead in the political race of the Indo-Pacific, wanting to keep China from getting the primary foothold in the coveted region, and to diversify its financial relations with other nations.

But Scholz’s willingness to invite China into the country’s critical infrastructure projects reeks of naivety; his refusal to understand the dangers posed by the Hamburg port deal suggests that Germany is still highly vulnerable to excessive Chinese investment and involvement. Even if the current compromise gives the Chinese giant below 25% of stakes in the project, as opposed to the initial proposal of 35%, the seed is enough for China to potentially take root.

Scholz’s willingness to go forward with the decision, despite disputes with parts of his own government, suggests brewing trouble. While Berlin is sticking to its claim of wanting to reduce dependency on China while maintaining ties with its largest trade partner, this path has proven to be a slippery slope in the past. It is up to the German people, and civil society, to gain control of a process now driven by huge business interests and appeasing political instincts. Much will depend on their success.

This article first appeared in EU Political Report on 11/01/22