By Huang Yicheng

Editor’s note: The Chinese resistance is more complex than it often appears to others. The ethnic and historical complexities of Greater China (a term itself that might draw dispute), the author contends, leave the Han Chinese majority as the odd man out overseas, and will continue to do so until the Han themselves come to grips with this truth.

In November 2023, Xi Jinping visited San Francisco. Major anti-CCP groups in North America gathered outside the venue, and fierce, bloody clashes broke out with pro-party groups. However, in this overseas movement, there is a phenomenon worthy of our attention, namely: exile groups from Hong Kong, Tibet, and Uighur can cooperate closely with each other, but they and the Han people’s movement are clearly distinct and even incompatible. Movement groups from the Han are basically unable to cooperate with Hong Kong, Tibetan and Uighur groups. Why? In the “post-white-paper era”” of China’s protest movement, what kind of relationship should Han diaspora groups maintain with anti-CCP groups from other ethnicities? This issue has become crucial. If we ignore it, the Han people’s movement will be increasingly marginalized overseas and its space for activities will become increasingly narrow. In the end, scattered sporadic, atomized “lone warriors” will be unable to form a joint force. To preserve synergy, a reliable narrative framework must be formed into which individual acts of resistance can be placed to tell a coherent story. The historical context of China’s border issues is extremely complex. However, within China, civil society’s space for political activities has been almost completely eliminated. Therefore, China’s internal complexities must be indirectly reflected in the relationships among overseas diaspora groups. And how we define the relationship between the Han people’s movement and those of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibetans and the Uighurs thus depends on our assumptions and vision for East Asia after the demise of the CCP. These assumptions and the vision we have for the future will determine what actions we will take now. During the white-paper movement, many people took to the streets out of a simple sense of justice. The participants in the movement had very different ideas. When any social movements temporarily ebb, they need to transform already-prevailing practice into theoretical thinking.

Tibetan, Hong Kong and Uighur groups together protesting Xi Jinping in the U.S.

Tibetan, Hong Kong and Uighur groups together protesting Xi Jinping in the U.S.

As the pressure of totalitarian rule within China becomes greater and greater, and the space for voices within China becomes smaller and smaller, to the point where the Chinese become completely voiceless, whether overseas diaspora groups can build an effective narrative has a great impact on the developmental direction of the resistance movement. The term “white-paper movement” itself was coined by overseas Chinese communities. For a time, Wikipedia did not use the shorthand “white-paper movement,” instead using the more neutral “movement against continuous dynamic clearance policy.” It was not until nearly a year later that the term used there became “white-paper movement.” In this process, we can see the overseas Chinese communities shaping historical memories. Since the white-paper movement and the June 4th movement were both nearly completely obliterated in public opinion in China, overseas Chinese communities are constructing a parallel version of history to compete for the right to speak with the CCP’s official historical narrative.

White Paper Movement demonstration, Beijing, Liangmahe

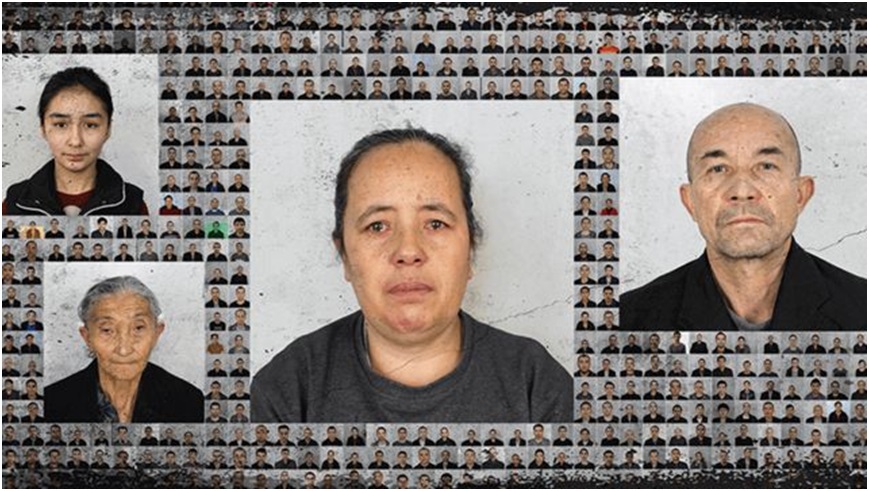

As everyone knows, what directly triggered the “White Paper Movement” was the fire that broke out in the Jixiangyuan neighborhood in Urumqi on the evening of November 24, 2022. The victims were mainly Uighurs. By the evening of the 25th, Urumqi citizens began to march in protest. Although we do not currently have sufficient data to reconstruct the demonstration scene in Urumqi that night, we can infer that the participants in the demonstration were mainly Han. The possibility of Uighurs among the demonstrators cannot be ruled out, but the main slogans were in Chinese. From July 17 to November 24, Urumqi experienced a brutal lockdown that lasted for more than 100 days. Citizens’ tolerance had reached its limit, and they rose up in anger. They took to the streets and attacked the city government. Violent clashes broke out with the police, as citizens demanded an immediate lifting of the lockdown. Images of the demonstration circulated online, attracting attention across the country and the world. Behind the magnificent social movement was the sympathy of Han citizens in Urumqi for the Uighur victims, and their anger at the lockdown measures imposed on them. But within this narrative framework, the Uighurs are even more voiceless. Since 2017, the Chinese government has built re-education camps in Xinjiang. According to reports from United Nations human rights agencies, more than 1 million non-Han people have been detained in them. Yet the Chinese government vigorously denies their existence. Due to thorough online censorship, Chinese people have no access to true information related to these camps. The Chinese government has further transformed the camps into an international political asset. Turkic and Islamic countries that have cultural and religious ties with the Uighurs, out of an independent desire to confront the West, must side with the Chinese government as long as Western governments support Uighur exile groups both for human rights-reasons and to use as a bargaining chip against China. In short, the Chinese government is trying to take advantage of this overturning of the usual relation between political culture and religious stance to turn the existence of the re-education camps in Xinjiang into a Rashomon incident. For Han people on the mainland, since they have no access to the truth, it may be understandable that they do not believe in the existence of these re-education camps; but for the Han citizens in Urumqi, when they see the Uighurs around them disappearing one after another, how do they feel? This question is very difficult to answer. But in short, in the current narrative about the white-paper movement in the Chinese-speaking world, the existence of the Xinjiang re-education camps is a fact that lurks under the water. The Uighur victims in the fire were a symbol that ignited the entire movement, but the Uighurs themselves were completely deprived of a voice. Therefore, overseas Uighur communities have a natural hostility to the white-paper movement. The Han people’s unilateral expression of sympathy for the Uighurs sounded completely misplaced to the Uighurs themselves. There was great discord in the two sides’ words, which created an even deeper gap.

2022 Urumqi demonstration

How to eliminate this gap and achieve mutual understanding between different ethnic groups is currently an important issue in our movement. Within China, the space for free expression is almost non-existent. Outside the country, such space is also very limited, but despite this, it is the only place where we can promote change. In 1989, the last important moment for China’s protest movement, such barriers were almost nonexistent. The nationwide pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989 indirectly helped the Dalai Lama win the Nobel Peace Prize that year. Similarly, Taiwanese and Hong Kong people at that time also generally participated in China’s democratic movement with a feeling that theirs was the voice of experience. However, more than thirty years later, the situation has changed immensely. Taiwanese, Hong Kongers, Tibetans and Uighurs have all constructed their own identities. However, the thoughts of many of the old pro-democracy activists have lingered like buried fossils since the moment they left China. They can neither integrate into American society, nor speak to people in contemporary China. Chinese society, which has undergone rapid changes in recent years, has left them behind, so their lives have become a lonely existence between the two societies of China and the United States. Therefore, they no longer have the conceptual ability to face the new reality. Among them, the most representative is Wei Jingsheng. In his article “The Debate on Uighur History” published by Radio Free Asia, he wrote: “Judging from the results of genetic testing, Uighurs are basically of the yellow race.” In fact, there is no such genetic component at all. There is no longer a concept of the “yellow race” in English, only the cultural concept of “Asian.” The former has been abandoned by mainstream academia as part of the old racist physical anthropology. And what is more, ethnicity is not the same as race. The concept of nation in the modern sense can never be reduced to genetic differences. According to Benedict Anderson’s theory of nationalism, nations are constructed through historical narratives. Any historical narrative needs to first suppose a theme, then form a narrative around this theme, and then this narrative in turn confirms the theme. This mutually reinforcing theme and narrative enable the construction of the nation. The own and the other exist by looking at each other, and who we are not defines who we are. During the Anti-Japanese War, the Chinese constructed themselves by opposing Japan. The concept of “we are not Japanese” defined “we are Chinese.” Similarly, Taiwanese people now use “we are not Chinese” to define Taiwanese identity. The two historical processes are the same.

The above analysis is in isolation too abstract. But if we combine it with specific historical events, it will be easier for us to understand the issue. In the era when the Kuomintang (KMT) dictatorially ruled Taiwan, it instilled the concept of “Chinese” nationalism into the Taiwanese people. The KMT set the Chinese nation as the subject of its history and formed a narrative based on the framework of the Three Sovereigns and Five Dynasties: Xia, Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing. This narrative in turn confirmed the theme of the Chinese nation. But Taiwanese used long-term social activism to end the KMT’s dictatorial rule, and then replaced the Chinese nation’s historical framework with a new narrative. The Taiwanese set the “Taiwanese nation” as the theme of history, and tell its history according to the sequence of aborigines/Dutch-Spain-Ming, and then Zheng/Manchu/Qing/Japanese rule/KMT/democratic constitutionalization. Behind the change of power from the KMT to the Democratic Progressive Party lies the change of ethnic culture. The older generation of Taiwanese received a historical education that focused on the Chinese nation, while the new generation of Taiwanese grew up receiving one that focused on the Taiwanese nation. The process of Taiwan’s democratic constitutionalization, the transformation of Taiwan’s historical education, and the construction of its national sense of self are actually different aspects of the same historical process. From the history of Taiwan we can learn from the process of long-term and sustained social movements condensing into ideological theories and cultural forms. Our social movement is still in its infancy, and we can learn many valuable lessons from Taiwan. It’s just that we must first abandon our China-centered ways of thinking and view ourselves just as the main body of Taiwanese people did, to wear their shoes so to speak. Only then can we truly understand their thinking.

In June this year, the present author met with Ambassador Shieh Jhy-Wey at the Taiwan Embassy in Germany. He told me a story. Ambassador Xie was born into a family of intellectuals from a mainland province. He had received a historical education focused on the Chinese nation since he was a child. He told me that when he first came to Germany decades ago, his German classmates asked him where he was from. He answered that he was from China. A German classmate asked him whether he had seen the Yangtze River, Yellow River, and Great Wall. Mr. Xie replied: I have never seen those, only the Sun Moon Lake and Alishan. The German classmate said: “Then you are from Taiwan, not from China.” Mr. Xie said this was a moment of enlightenment for his Taiwanese national identity. Later he joined the Taiwan independence movement and became an important figure in it.

Mr. Shieh Jhy-Wey, Taiwanese ambassador to Germany

The Hong Kong people’s sense of self was formed later than that of the Taiwanese. Even during the anti-extradition movement in 2019, the vast majority of demonstrators did not demand Hong Kong independence. The last of their “five major demands” only required the implementation of genuine universal suffrage. After the implementation of the National Security Law in 2020, many Hong Kong activists fled overseas, and the concept that “Hong Kong people are not Chinese” became mainstream. The mainstream of the anti-extradition movement is Hong Kong’s pure democrats. They only demand universal suffrage and do not emphasize the identity of Hong Kong people. But in addition to these pure democrats, there are also self-determination groups who believe that Hong Kong, as a colony of China, has the right to decide its own destiny. This group is represented by Nathan Law Kwun-chung. In addition, there are Hong Kong independence factions, represented by Ray Wong Toi-yeung. They also believe that the Hong Kong nation should establish its own independent country. This summer, this author helped plan an exclusive interview with the exiled Ray Wong Toi-yeung for the German magazine Mangmang, entitled “The Most Important Thing is to Maintain Identity.” In the interview, a reporter from Mangmang asked: “A slogan like Hong Kong independence seems impossible to achieve in reality. Why do Hong Kong people put forward such a political demand?” Mr. Wong replied: “Hong Kong independence is not only the ultimate goal of our politics, it is actually our ideal vision for Hong Kong and China as a whole. It is impossible for Hong Kong alone to be independent, because if Guangdong, Xinjiang and other provinces in China are not independent, we cannot be independent. First, we must define what independence is. There is political independence. There is also the idealized independence that we can be the masters of our own country and not be controlled by other external forces. This is a relatively abstract definition. Hong Kong independence can take different forms. We can be like other independent provinces in China — an independent country that is part of a larger political system, like the European Union. Hong Kong would then be independent in a political sense, but have a reciprocal relationship with other Chinese provinces.” Mr. Wong’s remarks are the answer to the question “How is Hong Kong independence possible?” Your author does not completely agree with this, because China’s provincial boundaries and cultural geographical units do not completely coincide. China’s provincial boundaries were demarcated during the Mongolian and Yuan Dynasties for the convenience of centralized rule. In provinces like Jiangsu and Anhui, which include places with vastly different cultures and levels of development from the provinces of Suzhou to Xuzhou, and from the cities of Huizhou to [a different] Suzhou, it is absolutely impossible to construct subjective consciousness and national identity within current provincial boundaries. Mr. Wong believes that the concept of “grand unification” should be eradicated. This author strongly agrees with this point, because the democratic system is closely tied to decentralization, local rule. We can use the European Union as a reference to envision the future of East Asia. However, Mr. Wong believes that it is impossible even to establish any independent country based on existing provincial lines. But this may be because he is not familiar enough with China’s geography.

Ray Wong Toi-yeung, German exile and Hong Kong independence leader

After the interview with Huang Taiyang in Mangmang, the Hong Kong diaspora magazine Like Water published an article by Joesph Lian, “You say you want to recover, but you don’t know what to do…?.” It mentioned the concept of a “Five-Independence Republic” and believes that Hong Kong people should cooperate with Taiwanese, Tibetans, Uighurs, and Mongolians and learn from them their experience in exile politics. In fact, there has been a lot of cooperation between overseas Hong Kong people and Tibetans and Uighurs, and Hong Kong people have also obtained a substantial voice for themselves internationally. But Mr. Lian’s article did not consider the question of whether Hong Kong independence is possible. Will Hong Kong exiles be forced to live abroad for the rest of their lives, never to be able to return to their homeland? Mr. Lian’s article does not consider what kind of political order should be established after the exiled Hong Kong people return to their homeland, so it is not as far-reaching as Ray Wong Toi-yeung’s. Despite this, the present author can understand Mr. Lian’s mood, because in the construction of Hong Kong’s national sense of self, as with Taiwan, “China” is used as the other. “Hong Kong people are not Chinese” constitutes the definition of “Hong Kong people.” Therefore, in this narrative, Hong Kong people’s dislike and rejection of Chinese people are necessary in the process of constructing Hong Kong people’s subjective consciousness. Mr. Lian wrote in the article: “Mainland people were oppressed by the anti-Wuhan epidemic measures for three years, but had no will to resist. Facing the return of the Cultural Revolution and Xi’s continuation in power, Chinese people at most can only hold up a few pieces of white paper and ‘lie flat.’ Finally, they understand that the evil and powerlessness hatched by Chinese civilization have become the norm.” This shows the author’s mentality: Hong Kong people have worked hard to support China’s pro-democracy movement for so many years, are thus exhausted physically and mentally, and in the end you Chinese people cannot stand up for themselves. Now Hong Kong people no longer have the energy to care about your affairs. Whether it is June Fourth, the pro-democracy movement or white paper, they no longer have anything to do with “we Hong Kong people.”

Finally, consider the overseas Tibetan groups. They are the group that has the best relationship with the Han people. In fact, Tibetan civilization was originally an independent civilization, on an equal footing with Chinese civilization, Japanese civilization, and Indian civilization. Yet if the Tibetan civilization, which originally had a feudal system, wanted to transform itself into a modern nation-state, this would also require a process of historical construction. However, due to Tibet’s geographical isolation, the entire territory was occupied by the CCP just as the modernization process had begun. It has been more than 60 years and three generations since the Dalai Lama led Tibetans into exile in 1959. The first generation of Tibetans in exile was born in Tibet, the second generation was mostly born in India and Nepal, and the third generation was mostly born in European and American countries. In such a long and vast history of exile, it is almost a miracle that Tibetans in exile have been able to maintain their own identity. But it is inevitable that the culture of Tibetans in exile has undergone great changes, and so is very different from that of Tibetans inside the country. However, the cultural products created by Tibetans in exile, including pop music and online videos, are widely accepted in Tibetan areas within the country, which creates a cultural bond between Tibetans within the country and those in exile. The Tibetan food celebrity on YouTube’s “Palden’s Kitchen” returned to Tibet using a foreign passport this summer. When he walked into the Lhasa Chongxai Kang vegetable market, the whole market echoed in the Lhasa dialect, “Palden is coming!” Many vegetable vendors and Lhasa citizens rushed forward to take photos with him. From this incident, we can see how widely the online culture of exiled Tibetans has been accepted in Tibetan areas within the country.

And yet the current Tibetan government-in-exile’s international influence has declined a great deal compared to 2008. Perhaps the three generations of Tibetans in exile can be represented by three groups: the first generation of Tibetans in exile is represented by the Tibetan government in exile, the second generation is represented by the Tibetan Youth Congress, and the third generation is represented by the Students for a Free Tibet (SFT). Theoretically, the Dalai Lama announced his withdrawal from politics and handed over legal authority to the Tibetan government-in-exile and in particular to the Tibetan parliament in exile. However, the elections of the Tibetan government-in-exile are limited to Tibetans in exile. If they return to Tibet in the future, it remains to be seen whether the government can be accepted by Tibetans. But whether inside or outside the country, whether men, women, old or young, the vast majority of Tibetans recognize the authority of the Dalai Lama. But he is now very old. If the Chinese Communist regime’s rule over Tibet were to end before the Dalai Lama passes away, it would be very likely that he could lead the exiled Tibetans back to Tibet and bridge the gap between various Tibetan groups and their rifts and disagreements. But if the Dalai Lama passes away before the fall of the Chinese Communist Party, divisions among Tibetans in exile may widen.

On the first anniversary of the Urumqi fire and the white-paper movement, we look back at the legacy of the contemporaneous social movements. In addition to the most important one, devoted to the end of the China-wide dynamic-clearance policy, three communities were formed overseas: “Hot Wind in New York (formerly known as the New York Democracy Salon), the China Deviants in London, and Germany’s Mangmang. Canada’s Citizens’ Association was established before the white-paper movement. These communities constitute several major concentrations of overseas youth. There are also some newly formed communities on the West Coast of the United States and in France, Italy, Japan, Australia, and South Korea. The concerns of these communities are very different from those of the June 4th exile group. Specifically, the overseas youth communities related to the white-paper movement generally lean left in their political stance, support feminism and the LGBTQ-affirming movement, and have a different view of politics. When it comes to their issues, most can abandon the limitations of Sinocentrism, and are generally very concerned about the problems of Tibetan and Uighur ethnic groups in Taiwan and Hong Kong, with whom they maintain relatively good relations. When I met with some American youth activists in Lithuania this winter, they told me about their experience in organizing events. Generally speaking, Taiwanese and Hong Kong people are the easiest to contact because of their similar cultures. Tibetans in exile are also relatively friendly, and they encounter the most obstacles when contacting Uighur groups. But if you start contacting young Uighurs overseas, it is often easier to get a friendly response.

Jewher Illhm at a “Hot Wind” forum in New York

Jewher Illhm at a “Hot Wind” forum in New York

Since this author has been engaged in political activities, he often held a self-centered perspective at the beginning, thinking that “we too are anti-communist. Why do you think that we have ‘original sin’ just because we are Han Chinese?” Feeling extremely hurt, he even adopted the attitude that “if China’s problems are not solved, your problems will not be solved either,” thereby arousing the disgust of others. But looking back, if we think from the perspective of the other side, Taiwanese, Hong Kong people, Tibetans, and Uighurs all construct their identities with “Chinese” as the other, so they naturally have a deep sense of China from the depths of their hearts. People feel disgusted. Although in fact the issues of Tibet, the Uighurs, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are all closely tied to the China issue itself, what right do we have to impose our issues on them?

Regarding the view of some Uighurs that Han people suffer from “original sin,” the author at one time agreed, but later changed his mind and believes that this was too simple. If the original sin of the Han people is now that they have not pursued justice for more than 30 years and instead pursue making money and economic development, are Taiwanese and Hong Kong people also guilty of this original sin? Without the existence of Taiwan and Hong Kong, China’s economic development would be impossible. Over the years, Western countries have invested in China and only made symbolic gestures on human-rights issues. Is this also an original sin? Because the narrative framework constructed by ethnic groups such as Taiwan, Hong Kong and Tibetans is “We Tibetans/Hong Kongers/Uighurs are persecuted by China, we are not Chinese,” their account is “persecuted by China” rather than “persecuted by the CCP.” At this time, if we “educate”” them that “Han people are also victims, and many Han people are resisting and are in jail, but the outside world cannot see it…,” this will only arouse their disgust.

In fact, the process of China’s integration into the world economic system after 1989 is a complex process in which economic interests and human-rights issues are intertwined. In this process, from Wall Street, American workers, Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong to the Chinese Communist Party, to the Han, Tibetans, and Uighurs, no parties are completely blameless. All parties are beneficiaries as well as victims. Confucius once said, “If a gentleman lives among the lower classes, all the evil in the world will be attributed to him.” It was originally a global, systemic injustice, but now any group in the “lower” position is designated to bear all the blame. Therefore, if the Han people really bear original sin, it means that we cannot form a community in the true sense, like Taiwanese, Hong Kong people, Tibetans, and Uighurs can. All links in the entire global chain will directly shift the blame to groups that are not allowed to build a community, that is, the Chinese/Han people. This is the structure of the idea of Han “original sin.” Most Chinese/Han rebels are “lonely warriors” like Peng Lifa [thought to be the person who was briefly able to drape a banner across a bridge in Beijing, before it, and he, were removed, not to be seen again] and are unable to form an effective community. This is not only the result of the Communist Party’s disassembling of mainland Chinese society, but is also related to the tradition of unification, household registration, and the imperial examination system in Chinese history, all of which facilitate individual surveillance. Although Tibetan and Uighur communities in Taiwan and Hong Kong continue to face failures, they are able to form stable communities, while pro-democracy groups are like a group of fragile bubbles. On the one hand, they have long criticized and accused each other, and on the other they wallow in self-pity in a fiercely confrontational posture, talking only to themselves. As a result, they are disliked by the Tibetan and Uighur communities in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and support for the Han people’s movement in the United States and other Western countries is gradually fading. The more resources decrease, the stronger the struggle of each of them to control and monopolize the remaining resources becomes. Therefore, various youth communities overseas must find ways to break out of these difficult conundrums and find a new path through the cracks, thereby enabling a different future.

We have to wait and see whether abandonment by the United States of the Han people’s movement and its support for the Tibetan and Uighur communities in Taiwan and Hong Kong represents a change in the United States’ vision for the future East Asian order. Furthermore, should we try to find new spaces for dissent? No matter how humbly we approach the Tibetan and Uighur communities, or those in Taiwan and Hong Kong, it is very embarrassing to be caught between them as Chinese/Han people. “China” was originally the overarching concept of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang, but for these communities it now exists as their opposing identity. When Hong Kong people, Tibetans, Uighurs and Han dissidents form a platform to talk about China’s human rights issues internationally, the position of Han dissidents is awkward. Only by constructing a narrative system with “China” as the other can the Han be integrated into the U.S. East Asia policy framework currently composed of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, and the Uighurs. During this year’s APEC demonstrations, Radio Free Asia reported on Zheng Yonghua, an activist of the Guangdong independence movement. In addition, Mr. Ho’s “Shanghai National Party” received coverage from the Wall Street Journal during the Shanghai lockdown in April 2022. Both are valuable attempts to break through the shackles of the “grand unification” framework that bedevils thinking about China among Chinese dissidents, and build a stable community. There are various other independent movements on Twitter, but they only exist on social media and have failed so far to build stable offline communities. For many, fanatical pursuit of the Chinese nation and the concept of its unbreakable unity occurs precisely because they have no community of their own, so they project their own identity anxieties onto this fanaticism for continued unification. For people who have entered a stable community, they will not only lose interest in the Chinese nation and its unity, but will also naturally feel a sense of disgust. The history of Taiwanese thought illustrates this point.

On the first anniversary of the white-paper movement, as the tide of social activism recedes, we don’t want to be a fish stranded on the beach, but should try to build a community. Otherwise the movement will die the death of floating bubbles that soon dissipate. As protesters born in mainland China, the reality we face is a society that is mired in quicksand, in a psychological state of mutual criticism and suspicion. It seems that we are caged in soft walls that make people unable to use their strength. Every day we face a strong sense of powerlessness. All our individual struggles are like single eggs hitting a high wall, unable to do anything meaningful as a joint force. It took a lot of effort to launch the white-paper movement, but now it is now inevitably dissipating in this way. The “China” that the Tibetan Uighur communities and Taiwan and Hong Kong hate and reject is a reality that we Han cannot escape and must face. Therefore, the difficulties we face are far greater in some ways than theirs, and the strength we can muster is pitifully small in comparison. However, the author has always believed that the constitutionalization of mainland China and the construction of civil society are the most important aspects of constitutionalization for the entire East Asia region. Only when we find our own way out will the way out for Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet emerge organically. Therefore, we may be able to comfort ourselves that we are bearing responsibilities for the greater number of people. We bear the most difficult tasks, the heaviest burdens, and the darkest realities. Thus, even amid our current powerlessness and melancholy, the struggle remains meaningful.

November 24, 2023

On the anniversary of the Urumqi fire

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247656&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The views of the author do not necessarily represent those of this journal.