By Bao Pu

Translated by Sonia Song

It is generally difficult, since ancient times, for biographical writings by family members of the deceased to be presentable or believable because they are difficult to remain objective. At least since Sima Qian, traditional Chinese biographies usually focus on “the character of a person”, namely depicting the behavior, temperament, and beliefs of the deceased.

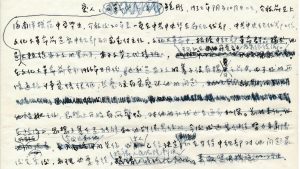

In the complex modern life, an individual’s life is divided into “public” and “private” aspects. The asymmetry of “public” and “private” information makes writing about the true “character” of the subject inevitably fall into a dilemma. Biography by family members may not be objective, yet biography by outsiders may lack sufficient understanding of the private side of the subject. Not to avert suspicion, I compiled this article, as the son of the biography subject, with the intention not to substitute but to supplement some missing information. Those that have been discussed publicly will not be repeated. In order not to lose the objectivity and fairness as much as possible, I try, in this article, to primarily provide original materials without comments. The materials include letters, oral recordings, video content and unpublished version of Bao Tong’s memoir (hereinafter referred to as “Bao Tong’s memoir”). (translator’s note: to be clear who is speaking, the author Bao Pu’s words are in italics; his father Bao Tong’s words in regular black; and his mother Jiang Zongcao’s words in regular blue).

Family Background

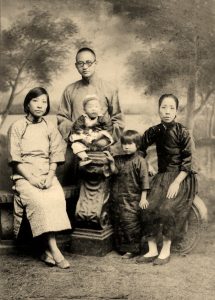

At the turn of spring and summer in 1928, on an uncertain day in anyone’s memory, my grandfather, Bao Peiren, an employee of Shanghai Yifeng Enamel Factory, married my grandmother, Wu Heng of Haining town. The wedding was held at the West Lake Hotel in Hangzhou. Thereafter, she gave birth to six children, and my father, Bao Tong, was the third one, born on November 5, 1932. The elders in the family gave him a nickname “San San” (the third).

The Yangtze River, originates from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, flows into the Pacific Ocean in Shanghai. That small piece of land in Shanghai was the whole world of my childhood. My ancestral hometown was in Suzhou, and I was born in Xiashi Town, Haining County, Zhejiang Province. When I was a child, with my parents, we fled to the French Concession of Shanghai to escape the Japanese bombing, and I was educated there. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In the autumn of 1937, the “July 7th Incident” struck Beijing. On August 13, the Japanese army bombed Shanghai, and then followed by the bombing of Xiashi town. The railway from Shanghai to Xiashi passing through Hangzhou was also bombed, so Haining was no longer safe. My mother took me, first fled to hide in Caojiawei in the countryside where ancestral graves of my mother’s family located and the tenant peasants of my grandfather and uncle all lived and worked there. The Japanese occupied Shanghai and Xiashi but did not go to the countryside often. Occasionally, when the Japanese soldiers came, the peasants would immediately alert us, so we could run and hide in haystacks.

After the autumn of 1937, my father came to Caojiawei once from Shanghai in a cold winter. He wrote the next spring, saying that we should move to Shanghai, and the whole family moved to Shanghai at the turn of spring and summer in 1938. We lived in Lane 4, No. 337 Rue Amiral Bayle in the French Concession, which later changed to Huangpi Road. Our family lived in two small shedrooms of about 20 square meters. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

In the autumn of 1938, I went to Minsheng primary school near my home, whose curriculum was too simple for me. From the second semester of the second grade, my mother transferred me to another primary school nearby called Chongshi. It was a good school and overcrowded with students. There I stayed until I graduated from the sixth grade. Then I went on to study at Chongshi middle school across the street from the primary school and where I studied from the summer of 1943 to the summer of 1946. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

I graduated from junior high school in the summer of 1946 and was about to enter Nanyang high school. Our family was unprecedentedly lively during that summer vacation, because my second sister, Linghua, reunited with us. She had gone to Wuhan with my uncle Wu Qichang when she was less than three years old. Then my uncle died of illness in 1944, and now after the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, my second sister finally returned home. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

Shen Xibin, the principal of Chongshi middle school, was a graduate of Shanghai Nanyang high school. He had an arrangement with his alma mater, to recommend the best junior high school graduates to high school every year. In the autumn of 1946, I was recommended to Nanyang high school, where I graduated in April 1949. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

Study and Self-Cultivation

During the summer vacation before entering junior high school in 1942, my father taught me to read “Mencius”, which opened a world of humanity for me. Mencius teaching helped me understand that people should treat others as human beings; otherwise, that person is not worthy of human being himself. In Mencius words: “Everyone has the heart of not being able to bear others’ sufferings! It is not human to be without compassion! It is not human to be without shame. ” Also, the people are first, the country second, and the emperor is insignificant. In Mencius words: “The people are the most important, the country second, and the king is the least!” (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In the summer of 1946, my uncle Wu Shichang, a professor at Central University, visited his friend Chu Anping in Shanghai. Uncle Wu was the most political one in the family. When the post-war political center transitioned to Shanghai, Chu Anping was planning to suspend the weekly publication Objective in Chongqing and start the Observation weekly in Shanghai instead. Uncle Wu was not only the columnist of the new weekly, but also helped with editing and then closed the Objective weekly in Chongqing. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

One day when Chu Anping came to my house for a visit, my mother cooked a pot of pumpkin for treats. At the dinner table, Uncle Wu pointed to me and said, “This is Bao Tong, and he loves to read”. Chu Anping took a note of my name and address and sent me a set of his magazines. Hence, these Observation weekly magazines, from its very first issue until it was banned by the Nationalist government Kuomintang, became an important source of my learning and knowledge. My parents brough this set of magazines to Beijing in 1966. Unfortunately, they were confiscated during the “Cultural Revolution” when our house was ransacked. (Bao Tong’s memoir.)

My cousin Xu Xuan was admitted to Washington University in St. Louis in 1947, and he left with me a copy of The Issues of Leninism by Stalin (printed in Moscow in 1940 by the Soviet Foreign Literature Publishing House). The book was extremely clear and easy to understand, and it inspired me a lot. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

I thought although this book was signed with Stalin’s name as the author, actually it must be a work of the theoretical propaganda team of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. So I asked my father, whether there was a wide gap of reading comprehension from the traditional Chinese “Four Books and Five Classics” to the imported trendy “ideology”. My father’s answer was: ” At that time I couldn’t understand the translated works of Lenin written by himself, but this book was easy to read, and I felt that what we believed in was not only a just cause but also it was scientific.”

In the second half of 1948, I often discussed literature and philosophy with Zhu Yulin, who was my classmate and roommate in the dormitory. He had an old edition of The Full Course of Dialectics translated from Russian, and I had a copy of The Essence of Historical Materialism by Professor Wu Enyu just published by Observation magazine. We exchanged the readings. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In 1953, when my colleague Song Yuanliang, an officer of the Organization Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Eastern China Bureau, saw that I was reading novels, he recommended that I read A Concise Course of the History of the Soviet Communist Party. He said, “It’s more interesting reading than novels.” The Chinese version of this book was printed in Moscow in 1953, also by the Publishing Bureau of Foreign Languages of the Soviet Union. After studying these two books, I became more advanced in my level of understanding of Marxism-Leninism compared with other colleagues in the CCP. What benefitted me later was that in the 1980s I gained the upper hand in every argument I had with Hu Qiaomu. (Bao Tong’s oral recordings, 2018-2020 ).

I never heard my father made one single negative comment on Marx and Engels. I remember once talking about Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Ownership, and the State, I said, “The subtitle of this book is On the Research Results of Louis Henry Morgan. In my view, Morgan’s research on The Ancient Society was quite influential at the time, but now it is almost historical garbage.” Father habitually rolled his eyes, which was an indication that we were not on the same page. He kept silent a bit, and then said: “I haven’t studied Morgan.”

My father was a staunch Leninist in his youth. The reading of A Concise Course of the History of the Soviet Communist Party did not change his habit of avid reading of all kinds of novels from ancient to modern times, from Chinese and the world classics.

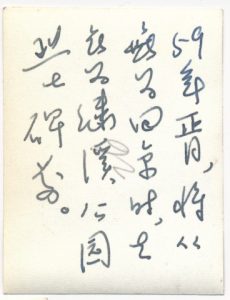

Write to me when you can, don’t forget. Decameron is fun and interesting to read. I read one episode each night, which helps me fall asleep.. ” (A letter from his wife Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on an unknown date in 1959)

Today I borrowed The Plum in the Golden Vase, recently purchased by the library. There are twenty-one volumes in total. You can read it when you are back. The print characters are large and there are many unsightly illustrations. I would not have borrowed it if it’s not for you. It should only be read for acquiring some knowledge, but not good if looked at too much. You will only have a few days to finish, what do you think? (Of course, it’s hidden at home now, wait until you come back?) (Jiang Zongcao’s letter to Bao Tong on December 12, 1959).

Modern Chinese history and martial arts novels were the two favorite categories of my father in addition to Mao Dun and Ba Jin. His was equally interested in novels by Gao Yang and Jin Yong. He said: “Reading Mr. Xu Yanping’s books can help one understand society and reading Mr. Cha Liangyong’s books can cultivate one’s temperament.”

In the summer of 1992, shortly after he was sentenced to seven years in prison, my father tampered with the famous couplet composed of the first letters of the titles of Jin Yong’s works by the author himself. My father re-arranged the orders of the letters and created a new couplet that he bragged to me, which also included all the titles of Jin Yong’s martial arts novels.

He also added a poem as a description of his summary of the reading:

Colorful romantic sentiments mixed with warlords failed endeavors.

Rich in metaphors and shining wisdom.

Full of compassion,

Not for the ghosts and spirits, but for the common fellow.

In 1993, my mother sent two sets of Gao Yang’s novels to my father in jail: The Complete Biography of Empress Dowager Cixi and Hu Xueyan. The following couplet was his comments after reading:

The officialdom, the business circle, the demimonde,

Vividly depicted;

The sacred path, the adventurous route, the underground way,

All so spectacular.

The years he spent in Qincheng Prison gave him more time to read novels. In 1994, I went home for a visit and randomly bought a popular novel The Tale of the Body Thief at the New York airport, which was the fourth book in the series The Vampire Chronicles by the American writer Anne Rice. I intended to read it to kill time on the plane but fell asleep after a few pages. So I didn’t know much about the story. Surprisingly, after I returned to the U.S., I received a letter from my mother, saying that my father wanted all the novels written by Anne Rice. What surprised me even more was that after my father was “released from prison in 1996 after serving his sentence”, he once showed me an intricate “vampire family tree matrix” that he had summarized when incarcerated, which was densely packed with small print. The Vampire Chronicles helped him to kill time in prison and also brushed up his ability of reading in English that he learned in middle school.

My father liked Professor Yu Yingshi very much and had occasional communication with him. I remember that Prof. Yu’s “Explanation of Chen Yinke’s Poems and Essays in His Later Years” made him look enraptured. He said, “Yu Yingshi got the mocking of the Communist Party from Chen Yinke’s poems and essays in his later years. I didn’t see it. So obviously he was smarter than I.”

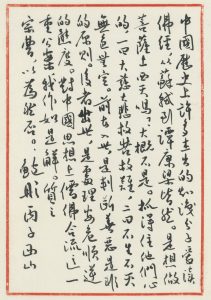

In the last twenty years of my father’s life, I was able to visit Beijing about once a year during the Spring Festival. I could see that over the years, more and more traditional classic books piled up in his study. He studied Buddhism for a while and loved to talk with me about his learning in reading scriptures. Since I had no knowledge of Buddhism, I couldn’t remember anything important. Fortunately, he left this handwritten note:

“Many outstanding intellectuals in Chinese history love to read Buddhist scriptures, from Su Shi to Tan Sitong, Kang Youwei, and Liang Qichao. Did they want to go to heaven as a Bodhisattva? Probably not. The two things that grasped their hearts are: firstly, merciful compassion to save the suffered and sufferings; and secondly, their understanding of do-nothing and the emptiness. The former is about getting involved, the principle for judging good and evil, right and wrong. The latter is about an attitude of being detached and letting nature take its course. This is how I explain the important case of the integration of Confucianism and Buddhism in the Chinese way of thinking. (unpublished Bao Tong’s calligraphy)

I have never tried calligraphy so father seldomly talked about it with me. I only remember him saying that “calligraphy lies in its relaxed free flow and reflects the artist’s own style and personality.” Wang Xizhi’s Preface to Lanting Collection was completed in one go. The three typos did not prevent it from being immortal.”

My father’s eyesight got weaker due to age-related macular degeneration, and he asked me to transfer some of his favorite books to the tablet so they could be read in enlarged print. These books included Lecture Notes on the History of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Annotations of Zhuangzi’s Writing, The Analects of Confucius, Annotations of Book of Rites, and Annotations of Mencius etc. Noticeably, among the Chinese classics, the writing of Confucius, Mencius, and Zhuangzi were his favorites.

After about 80 years old, my father collected seven or eight versions of “The Bible” in various Chinese and English publications. In the past few years, he asked me to search for various audible versions to install in his computer. He also participated in a few “Bible” seminars in Beijing. Some people even persuaded him to be baptized. However, based on what he said to me about Christianity, I suspect that his interest in studying the Bible was to find a new faith. For example, he once said: “The childhood education of Maxim Gorky made him feel that there are two Gods in the Bible. The God in the Old Testament is grumpy and frightening; yet the God in the New Testament is like a kind and benevolent Father. I feel the same way.” He also said, “Jesus was a social reformer” and I responded: “What kind of Christian revisionism is this?” He rolled his eyes and expressed displeasure at my frivolity. I see there were also two fathers in my family, one was impatient, arrogant, and stubborn; and the other was loving and wise.

Bao Tong and the Chines Communist Party (CCP)

The Constitution of the Republic of China was adopted in 1946. In the same year the civil war broke out. Thus, the national government did not have time to implement its goal of “putting down the chaos and saving the country”. Otherwise, political ideals could be realized through measures of “protecting the constitution”. Since the Revolution of 1911, Dr. Sun Yat-sen embedded an idea in the mind of the Chinese people saying that China’s problem was that people were too scattered like sand, if they got united, any problem could be solved. Wu Shichang also believed that China’s situation at the time called for rebuilding authorities. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

I aspired for equality and made it a goal of my pursuit. A popular song at that time goes: “There is a good place over the hill where the rich and poor alike”. The name of the Communist Party sounds the same way to me. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

I first came into contact with the CCP in the winter of 1946. At that time, my best classmates were all pro-Communist, and some were already members of the underground CCP. We had reading and discussion meetings almost every day. I remember participating in the event of “Welcoming the Horse” launched by the CCP to welcome George C. Marshall to China to mediate the military conflict between the Nationalist Party Kuomintang and the Communist Party to prevent a full-scale civil war in China (translator’s note: the first syllable of the Chinese translation of “Marshall” is the same character of a horse). After the “mobilization to put down the chaos”, there were certain pressure and danger to be pro-Communist. I then wrote a poem entitled “The Thermometer”, in which I said: ” With one’s own crimson blood show the existence of warmth in the world. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018 to 2020).

The entire poem goes:

Standing in a lonely corner,

Bravely endure the teasing of fate.

Dedicated to working for others,

Until the minute it breaks.

Aloof and stern,

Facing the coming of chills.

With one’s own crimson blood,

Show the existence of warmth in the world.

This poem was published in the upper right corner of the Culture General page of Shanghai Daily Ta Kung Pao in late 1948 or early 1949. I kept the clipping of this until when my house was ransacked in August 1966. (See the article A Broomstick, People’s Daily Press, 1988).

My way of accepting the CCP was somewhat different from other people who accepted it as a fait accompli, when the Communist Party seized power and established rule with the barrel of a gun. But I joined the Communist Party voluntarily as a pursuit of my ideals. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020)

At the beginning of 1949, my schoolmate of Nanyang high school Jiang Shuming asked me: “What do you think that China’s hope lies?” I said, “China’s hope lies in democracy.” He then asked, “Who do you think can practice democracy?” I said “the Nationalist Party may not be able to do it; and the Democratic League is too weak; but the Communist Party is powerful.” Jiang fully agreed. Later, when Jiang introduced me to join the CCP, he asked me to write about my understanding of the Party. What I wrote on a piece of an exercise book paper was roughly the same. (Jiang committed suicide by jumping into a well during the Cultural Revolution). (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

A few days after that conversation, Jiang told me: “Someone representing the CCP would talk to you tomorrow morning at seven o’clock in Petain Park (now known as Hengshan Park). You should hold a copy of Ta Kung Pao in your left hand, not necessarily of that day, but showing the headline. Someone will come and ask you what time it is, and you will answer: I don’t have a watch, it’s probably seven o’clock.” (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

Thus, the next day, I got in touch with the CCP organization. Later I found out that the person who came and talked to me was Zhang Xiaojun, the head of the CCP Organization Department of Shanghai South School District One. After talking with Zhang, I took an oath to join the Party: to fight for communism all my life; to put the interests of the revolution above all; to abide by the Party discipline and strictly keep the Party’s secrets; to implement the Party’s decisions; to be an example for the masses and to learn from the masses. Upon parting, Zhang took out a piece of paper from his leather shoe and handed it to me. It was an article written by Chen Yun in 1939, How to Be a Communist Party Member, which contained the content of the oath. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

Thus, April 12, 1949, became a significant day in my life. On that day, I felt that I was like a drop of water that had integrated into the torrent of communism striving for the liberation of all mankind. In an instant, I seemed to have transformed from a state of just being to taking conscious actions. From then on, life had an unprecedented meaning of purpose that I had never realized before.” (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

The People’s Liberation Army took over Shanghai in May 1949. In June, the Organization Department of the CCP East China Bureau required all underground party members of Shanghai to do an official registration. That was the first time in my life to fill out a form. I took it seriously and wrote neatly. When the People’s Liberation Army was advancing south from Shandong, it urgently needed to recruit cadres. There were more than a dozen boxes of cadre files that needed to be sorted out. Probably because the underground party members in Shanghai generally had a higher level of education, The CCP Organization Department of the East China Bureau asked the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee to send seven underground party members from Shanghai to work in the East China Bureau to sort out the files. There was only one criterion: good handwriting. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

One day at the beginning of July 1949, I was taking an exam for becoming a journalist in the morning and was to continue the exam in the afternoon. Around noon time Liu Fengfei came and informed me that I was transferred to work at the Organization Department of the East China Bureau. I had no idea what that organization was, neither did Liu. She only knew it was a “superior body”. I said to her,

“I am taking the exam for reporters and will be done in one and a half days.” Liu said, “This is a Party organization’s decision, so go!” I asked: “Where and how?” She told me: “Go to the school district party committee to finish the formalities.” I didn’t know what the “formalities” were but since the Party had made the decision, so it was quite simple and easy. In the afternoon, I went to the school district committee and met the leader Qian Qichen who wrote a note on a piece of scrap paper: “Municipal Youth Committee: Comrade Bao Tong, a member of our party, is going to work in the Organization Department of the East China Bureau, please transfer his organization relationship. ” And then signed his name. Originally, the transfer of relations was a matter handled by Zhang Xiaojun, the organization committee member, but Zhang was not there, so Qian did it for him and wrote the note. This way, I went from the District School Committee to the Municipal Youth Committee, and then to the East China Youth Committee, one step at a time. In the evening of the same day, my organization relationship transfer was completed at the Organization Department of the CCP East China Bureau. (Bao Tong’s oral recording 2018-2020).

The temporary office of the East China Bureau was located in Jianshe Building, a 17-story building on the southwest corner of Jiangxi and Fuzhou Road intersection, which originally was the office building of the “China Construction Bank Company” in Song Ziwen’s consortium. After reporting for duty, I was given a note certificate for entering and exiting the agency of the “Second Detachment of Huaihe Army “, the pseudonym of the East China Bureau at that time. For the sake of keeping its secrecy, the East China Bureau was called the “Second Detachment of the Huaihe Army”, following the army sequence when it went south from Shandong. I was told: “Come to work tomorrow morning… and you will live here from now on. There are camp beds here, but you need to bring a quilt from home.” (Bao Tong’s memoir).

It was late evening when I got home that day, and I told my parents that I was going to go to work and live there the following day. Father didn’t say anything. My mother was stunned and asked, “So you will not go to school anymore?” I replied, “No more.” Before joining the Party, I was a student, and studying was my bounden duty; after becoming a party member, revolution was my new bounden duty. This was the belief of the son, but the mother was a little sad. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

Early next morning, I rolled up a thin quilt and left home. I walked from Baylor Road to Fuzhou Road, humming the song “our army is here” along the way and thus started my revolutionary career. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

Among the seven of us selected, three men and five women, two were college graduates and the rest graduated from high school. One of the men was Gu Weiqing, the son of GuYuxiu, with whom I had the best relationship. Gu had opinions on everything, and I had none on anything. So I would always follow him around. Thus, I joined the Organization Department of the East China Bureau from July 1949 until early 1954 (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

I was very excited when started working at the CCP East China Bureau. First, I felt that I was discussing important national issues. Second, everything was freely discussed without any taboos. It was even possible to say that Mao Zedong did not represent the Communist Party. During mealtimes, eight of us were seating around a pot of food, freely assembled and could discuss various issues freely. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

The CCP immediately stopped recruiting new members after taking over the power of the whole country. According to Liu Shaoqi’s words, we used to be controlled by our enemies who helped us manage the party well. At that time cowards and non-revolutionaries did not dare to join. After taking over the power, all opportunists and ambitious schemers with various motives wanted to join the party, even just to find a job. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

The non-recruitment policy ended in 1951 when “land reform activists” were admitted to the Party, which was fine. But during the period of the “Great Leap Forward”, “those who are good at lying joined the party”. It was surprising and absurd. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

I witnessed a scene in Ningxia in 1959. Yang Cang (former secretary of a prefectural party committee in Guangdong) chatted with me and talked about the conflict between him and Li Jingying, the first secretary of the provincial party committee during the “anti-rightist movement” in 1958. He said that Li wanted the grain output to be 1,000 catties per mu, and I said 800 catties, so I was considered as “inclined to the right”. But the actual yield was only 400 catties per mu, which meant that both of us were “inclined to the left” and he was even more so. In the end I was labeled a “Right Opportunist”. What he said made a deep impression on me that I will never forget (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

In 1950, a “Delegation of Party Organization Workers” visited the Soviet Union led by Zhang Xiushan, the second secretary of the CCP Northeast Bureau. The delegation was received by Otto Wille Kuusinen, head of the Organization Department of the Soviet Communist Party Central Committee. He gave a presentation about the internal setup of the Soviet Party’s organizational structure. Under the Party, there were professional management departments such as the Ministry of Industry, of Agriculture, of Transport, and of Planning, Finance and Trade, etc. This is where the CCP imitated the Soviet Union’s model in party leadership (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

I went on a business trip for the first time in the winter of 1951, from Shanghai to Jinan, to attend the statistics work meeting of the CCP Shandong bureau led by Kang Sheng. In 1953, learning the cadre system of the Soviet Union, as one of the team members, I was sent to the Shanghai Electric Machinery Factory for practical training. The team was led by Zhou Baorui (later director of the Foreign Affairs Office of Shandong Province) and Yin Bangchang. In the same year, following the Soviet Communist Party model, the CCP, within its Organization Department established the Industrial Management Office, Transportation Management Office, Finance and Trade Management Office, and Culture and Education Management Office, and thus created a party organizational structure that controlled all aspects social life. The CCP Organization Department ordered that 100 cadres above the county level be transferred from the Organization Departments of the six CCP local regions to the Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee to strengthen management by trained cadres. The East China Bureau recommended three of us, including Li Jun, head of the HR division, Gao Cimin, and myself. So at the end of 1953, I was transferred to the CCP Central Organization Department (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

When the news of Stalin’s death reached Beijing in March 1953, my father burst into tears. This was what my father told us but my sister and I never saw him crying on any occasion.

On April 27, 1957, the CCP Central Committee issued the “Directives on the Rectification Movement”… I actively responded to the call of the Party Central Committee and signed up to go and work in the countryside. In early May, the Organization Department approved five people to go to Zunhua County, Hebei Province for remolding through labor. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

The agency is engaged in the Anti-rightists drive and we must study until the beginning of August. We have many questions. For example, is the nature of the rightists a problem among the people, or one between us, the people, and the enemy? Are rightists one of the broadly defined categories of left, center, and right? I mentioned these two questions at the party’s group meeting, but I am still not satisfied with some people’s explanations. Because I think, this anti-rightist drive is by no means a problem among the people but should be regarded as one between the enemy and the people. But it seems that the central government is handling this issue as it is a problem among the people. I have been thinking hard but can’t figure it out. What do you think? (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on June 31, 1957 (author’s note: this is the original text).

I returned to Beijing in July 1957 when the remolding through labor was over. Before I had time to report my experience in the countryside to the Party, I was involved in the “anti-rightist drive” and became the target of the movement. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

The Party asked whether I had the thinking or words like a Rightist. I said yes. I sympathized with all the Rightists and resonated with their opinions. The Party said this was not a joke and if I had any evidence. I said that I had taken some notes and they were absolutely true. When I was laboring in the rural areas, some people made complaints and I thought what they said was right and I took notes. In addition, I thought that the propositions of Zhang Boju, Luolongji, Chu Anping, and Fei Xiaotong were all pretty good and I recorded it clearly in my diary. The Party had no choice but to begin criticizing me and it was last from August 1957 when I returned from laboring the countryside to January 1958. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

“I have been working in the municipal government of Beijing and had no contact with the Central Organization Department. One night at one of the Party’s meetings (which were usually held in the evening so as not to take up anytime at work) someone suddenly proposed that Wu Linghua should talk about her younger brother, who was a big Rightist in the Organization Department and was being criticized. I didn’t know about it and was stunned. Then the meeting changed the subject. Later it was clarified and over. I asked Bao Tong afterwards and he said, “I confessed it myself.” (According to the recollection of Bao Tong’s second sister Wu Linghua )

During the Cultural Revolution, a big-character poster alleged that Minister An Ziwen, Director of the Cadre Management Office Liu Zhiyan, and Director of the Research Office Zhao Han (both ministerial committee members) shielded me and made me “slip through the net”. I believed that it was possible for Liu Zhiyan to “cover” me, for he really cared about me. But I met Zhao Han in 1958, and An Ziwen in 1960. Since they didn’t know me at that time, it seemed unlikely that they would cover up for me. No matter who was covering me up, in January 1958, the Organization Department decided that although I had committed a serious pro-Rightist mistake, I could be given a lenient punishment and be exempted from the Party discipline. Therefore, I and some other 30 cadres who needed to remold were sent down for labor led by Zhao Han, a member of the ministry’s Party committee. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In early May 1958, the Anhui Provincial Party Committee asked us to move to Wuwei County on the banks of the Yangtze River. This county was large in size and abundant in resources with one million people and 1.8 million mu of cultivated land (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In order to achieve the “Great Leap Forward”, Anhui Province adopted a “contract system”. Zeng Qingmei, the deputy head of the provincial party committee, who was also the former subordinate of Li Xiannian, issued an order, promising to change the situation of Wuwei county within one year. Zeng Qingmei learned that there were cadres from the CCP Organization Department in Anhui, so he asked for those cadres be transferred to help him to achieve his goal. So, on May 5, we all went to Wuwei County. I remember this date clearly because it was Marx’s birthday (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

Wuwei was a large and abundant county with a population of one million, adjacent to the Yangtze River. Both Zhao Han and I visited the Township Agricultural Production Cooperative in Wuwei County. The Great Leap Forward and the People’s Commune Movement all impacted this town, and this was the place where the excessive grain acquisition was levied. Before leaving the county, we had a big quarrel with the county party committee. Later, the county party committee complained to the Provincial Party Committee, saying that those from the Organization Department were “quitters”, and that I was a “trouble-maker.” (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

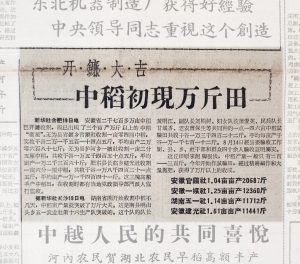

On August 20th, the national newspaper People’s Daily published the news that Anhui Province, including Guanzhen Township where I happen to work there, created a miracle of producing unprecedented rice yield per mu of land. At that time, I didn’t know that this was orchestrated by the Provincial Party Committee behind the scene. That “miracle field” was next to the Zhenhe Agricultural Cooperative where I worked, and the people came to tell me that the “miracle” was fake. (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

What they did was to pull out the rice from ten mu of land, planted it on one mu of land, and then harvested it five days later. At that time, I often heard about agricultural high yield “miracles” all over the country, and I believed them to be true. But when I saw the fake miracle in Anhui, I wrote a letter to the central government. (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

I said in the letter, “All over the country everyone is excited about the current situation of the Great Leap Forward but there is a very bad phenomenon in Anhui: the false miracle. The “Zhenhe Agricultural Cooperative” where I work is adjacent to the “Guanzhen Agricultural Cooperative” where the miracle is created, only a few miles apart. I know that ten mu of rice is transplanted to one mu of land, and then harvested five days later to count for the yield output. This kind of falsification is an evil trend, and has a very bad influence on the local people, which also tarnishes the reputation of our party’s “Great Leap Forward”. (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

One day, Duan Xuefu, the head of the Sixth Division, was named to attend a teleconference of the Provincial Party Committee. I just remember that Duan Xuefu came back and said in a panic: Bao Tong! You are causing trouble! It turned out that the conference call was for Chen Qizhang of the General Office of the CCP Central Committee to listen to the investigation report of the Anhui Provincial Party Committee on the content of my letter. (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

Zeng Xisheng, the first secretary of the Anhui Provincial Party Committee, was in Beidaihe, so Huang Yan, the governor of Anhui Province, attended the conference call. Huang said: “We received calls and documents from the central government and took them very seriously. We immediately sent Zhang Shirong, a member of the Standing Committee of the Provincial Party Committee and head of Rural Affairs, to investigate. Now I ask Zhang Shirong to report. I have a cold today, so I will stop talking now.” Zhang Shirong continued and said, “I did not notify any cadres of the prefectural or the county party committees but directly contacted local people immediately. According to the local people, it is true that the crops of ten mu of land were merged, but the purpose was not to cheat, but to fight against drought. Nine mu of highland were dried out. In order to save the crop, the people merged the crops into one mu of land that had water. Therefore, the situation reported by Bao Tong is untrue (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

Not long after, Li Buxin, the head of the Political and Legal Cadres Division, came to Anhui and said to me, “Minister An specifically asked me to tell you two things. The first is that the situation is already clear; the second is not to mention this again.” I said, “That thing is obviously fake, how come it cannot be mentioned anymore? ”Li Buxin explained: “Didn’t I just tell you?!” I was stunned. Li Buxin repeated, “It’s Minister An’s instruction not to bring it up anymore.” Then we both laughed, for we knew that Zeng Xisheng was trusted by Mao Zedong, and this issue should be resolved at the higher level (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

“I’m very interested in the People’s Commune. Maybe it is also organized in the place where you are? It seems that once the People’s Commune is established, we will enter the society of communism. You are lucky to have access to these new things. Please tell me something about this when you get a chance.” (Letter from wife Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on August 26, 1958).

In 1959, when I came back from Anhui, Liu Zhiyan asked me: “Do you think you have learned anything?” I said: “I have come to the conclusion that if I disagree with the views of the Party Central Committee, then it must be me who is wrong.” Liu Zhiyan replied: “No need to be so sentimental.” (author’s note: the original meaning in Chinese refers to intentionally distorting one’s feelings and concealing one’s true feelings.) In 1967, I was locked up in a “cowshed”. The rebels from Sichuan found me and asked me to expose Liu Zhiyan’s wrong doings, and they told me that Liu Zhiyan had committed suicide “against the Party”. (Bao Tong’s recording, 2018-2020).

After the “Great Leap Forward”, for three consecutive years, tens of millions of people died of starvation, which had nothing to do with natural disasters or the fertility of the land. Later it could be seen that wherever the “three red flags” were raised the highest, the anti-right deviation launched the strongest, and exaggeration was the most prevalent, where people starved to death the most. The root-cause was that exaggeration led to false reporting of grain production, but the state requisitioned grain according to the false reporting of production, which inevitably encroached on the normal rations of farmers, causing a large number of farmers to starve and suffer from hunger and cold when food was in short supply. Therefore, the cause of tens of millions of people starved to death was political. I have not done any special research on how many people died of starvation in the whole country, but I did hear two figures mentioned. (1) In 1962, Li Xiannian told Wang Weigang, a member of the Central Supervisory Committee, that he estimated that: “The number of starvation deaths in Anhui Province is between 3 million and 5 million.” I learned this from a colleague in our office who went to Anhui to inspect work with Wang Weigang. (2) Guangshan County in Henan Province had a population of 300,000 before the Great Leap Forward in 1958, but only 100,000 remained at the end of 1960, a decrease of 2/3. This figure surfaced with the exposure of the Xinyang problem. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

In 1963, I suddenly heard about a “Report on Lei Feng’s Deeds” in the Organization Department. It struck me deeply. I thought it was such a weird thing as publicizing what good deeds someone did every day, arranging good deeds in advance, taking pictures, and bragging publicly. Later, Chen Yonggui came out as a hero, and more and more such things. It has taken the Communist Party a long process to form the habit of habitual lying. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

On April 16, 1992, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection sent two department directors and a staff member to Qincheng Prison and read to me the decision of the CCP Political Bureau to expel me from the Party. This decision of the Politburo accused me of “serious violations of the criminal law”, but did not provide any facts, making it impossible for me to refute with facts. However, this decision had two fatal flaws: it was neither in compliance with the CCP Party Constitution, nor was it in compliance with the “Constitution of the People’s Republic of China” and relevant laws. (Bao Tong’s memoir)

According to the decision, my position as a member of the CCP Central Committee was not revoked until March 1992. Didn’t this mean that during the 2 years and 8 months between May 28, 1989 and this decision, legally I was still a member of the CCP Central Committee, but I was illegally imprisoned! This “decision” claimed that I had “seriously violated the criminal law”, so I asked: “What crime did I commit?” The person who announced the decision banged table and said, “You should be clear yourself! In return, I banged the table too and said, “Is this how the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection works? Is this your work style?!” (Bao Tong’s memoir).

For my father, emotionally, the decision of expelling him from the party was worse than the seven-year sentence in jail. For this, he wrote a letter of appeal to the Standing Committee of the CCP Central Committee as well as Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun. Although he said afterwards that “he parted ways with the Communist Party since that day”, I could tell that in his heart he still couldn’t let go of it.

I was taken out of my cell at midnight on May 28, 1996 and was taken to a small room on the west side of the south gate of Qincheng Prison. There was a table in the room and on the table laid a paper with black characters and a red stamp of “Qincheng Prison”. In the center of the stamp was a five-pointed red star symbolizing the Communist Party of China. And this white paper with black letters and a red stamp was the “Release Certificate by the Ministry of Public Security”. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

After the guards read the release certificate to me, Tang Guoqing, Director of the Supervision Department of Qincheng Prison, and Zhang Yuan from the Beijing Public Security Bureau came to talk to me. Later, I learned that there was no such person as Zhang Yuan in the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau. He was the deputy director of the First Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security. I had no idea why they talked to me unidentified. And why did they bring me out at midnight? That’s because I was brought in on May 28, 1989, and later was sentenced for seven years.

As of 24:00 on May 27, 1996, it would have been exactly seven years. And for more than a minute, it would be a violation of my human rights. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

The “out of prison” at midnight on May 27, 1996 was a big joke. Because my father could not go home after being “released from prison”, but was illegally detained for another year, at the “Xishan Management Office of the State Council Logistics Administration”, known as “Xinglin Villa” to the outside world. Unlike prisons, there at the “Villa”, family members could visit and stay with the inmate. Below is what I witnessed firsthand while I was there with my dad.

From the minute when “released from prison”, it was the day when my father began to “defend his rights”. My father had an argument with an official sent by the CCP General Office. With his mouth twitched, this person said angrily: “Aren’t you just saying that the Communist Party violated the law? Even so, what does that have to do with me?” Bang! My father hit the table, rolled his eyes, the whites of his eyes flickered, and finally swallowed a sentence I was familiar with: “What do you know?!” After the man left, he said to me: “The Mensheviks were still a political party in the normal sense; and the Bolsheviks deteriorated from ‘total lies’ to ‘total illegality’; in the end it turned into a gangsterdom.” Seeing his livid anger, a mocking sentence rushed to my lips: “So you just get it now? ” Yet under the circumstance I could not say it to him. This was the harshest criticism I have ever heard from him of a Leninist party.

My father never negated the justification of his joining the CCP. He said, “If my choice back then was wrong, it was because the whole world was making a wrong choice at that time.”

About ten years ago, one day when browsing through books and newspapers, I came across an exclusive interview report about my father by Ian Johnson, with a catchy title “I would have been a corrupt official too if I were still in the party system.” (The New York Review of Books, June 14, 2012).

According to my observations, it took quite a long time for my father to realize that the Communist Party he had joined “voluntarily to pursue an ideal” simply disappeared without a trace, since no one knew exactly when. His well-known statement on “Guo Wengui is my teacher” proved this, which was about in the second half of 2017:

“Guo Wengui is indeed my teacher, who opened my eyes. I used to wonder what color the Communist Party is. I have always thought it was red, until when Guo Wengui told me it was black, which opened my mind. It never occurred to me that the Communist Party was actually black. (Internet video clip)

Love and Marriage

“Comrade Zong Cao: I’m exhausted … On the morning of the 22nd, my watch glass was broken, so I walked along the main road and turned to Weier Road to a watch repair shop to have it replaced. I entered a small room with a table in the corner and a young man was working at the table. Next to the table was a bed plank where two learned men sat there chatting. One explained to the other the ‘big policy’ of ‘four friends and three enemies’ (see note below): ‘This is the biggest policy of all! If you don’t learn this, you will only know that Chairman Mao and the Communist Party are good, but don’t know why. Only after you learn about this will you understand!’ One of them was the shop owner, and the other a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine. They were so much into the conversation like close friends, which showed that our work has really penetrated into the masses of the city streets! ”(Letter from Bao Tong to Jiang Zongcao in the winter of 1951).

This letter in the winter of 1951 was the first one that my father wrote to my mother Jiang Zongcao during a business trip. This letter would seem weird by today’s standards if it was meant to court a girl. The letter took a form of “travel notes” reporting local conditions and customs, and its content was about the “propaganda effect” of the Communist Party’s policies. The historical background needs some explanation: In June 1950, Zhou Enlai said at the Third Plenary Session of CCP’s Seventh Central Committee: “In the new era, we must be clear about the three enemies (namely imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalism) and four friends (namely the proletariat, the peasantry, the petty bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie). The central issue today is not to overthrow the bourgeoisie, but how to work together with them.”

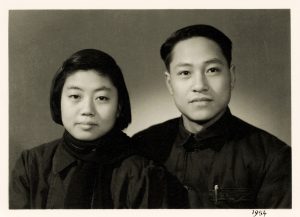

In the autumn of 1954, Jiang Zongcao was admitted to the Russian Department of People’s University of China, and also moved from Shanghai to Beijing. I went to see her every Sunday. Not long after school started, she was found to have tuberculosis and was asked to leave the school. According to the rules, she should return to her original unit, but the East China Bureau had already been dissolved. So I went to see Li Jun who readily said that she should come to work at the Central Organization Department. Thus, Jiang was transferred to the Division of Cadres in the Organization Department. (Bao Tong’s recording 2018 to 2020).

At the end of 1954, the Organization Department arranged for Jiang Zongcao to receive treatment at the Heishanhu Lung Disease Sanatorium in the suburbs of Beijing. she was cured and discharged from the hospital in the spring of 1955. Her former roommate was worried to be contracted an infectious disease and didn’t want her to move back. She had no place to go. Therefore, we simply decided to get married. The date was set on the day she was discharged from the hospital, which happened to be April 12, the second “4.12” in my life. (Bao Tong’s memoir).

April 12 is a very special day for me: on April 12, 1949, I joined the Communist Party of China; April 12, 1953 was the first time that my article was published in the “Liberation Daily”; April 12, 1955, I married Jiang Zongcao. On April 12, 1968, I became a “black gang member” in the Cultural Revolution and I received a ban: “Not allowed to go home from now on.” (Bao Tong’s recording 2018-2020).

I completely agree with the views on love that you wrote in your letter. What is love after all? A quote from Henry Fielding states: “…there is a kind, compassionate disposition in people’s heart, which finds satisfaction in enhancing the happiness of others.” …Love is not only to enhance the happiness of others, but oneself also obtain satisfaction and happiness in doing so. It is a rare and precious feeling. Ture love is based on enhancing mutual happiness. It is really a pleasure if handled well. Ding Ling seems to have said: “If one handles love well, then not only does one feel that the world is wonderful, but also a person is lovely, and there is light and joy everywhere, and life is so fulfilling… This kind of relationship is mutual understanding, mutual respect, and mutual affection, moving forward hand in hand…” Of course, for Communist Party members, there should be also other criteria, namely beneficial to the revolution, work, and personal happiness. (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on February 28, 1955)

It is difficult for people today to fully understand the reverse practice of being comrades first, then getting married, and then falling in love. Most of my father’s letters have been lost, probably because of house raids during the Cultural Revolution. But I somehow know what “some views on love mentioned in the letter” were and where they came from. Years ago, my father recommended a novel to me, What Is To Be Done by Nikolay Chernyshevsky, saying it is “the most moving love story ever written.” It is doubtful how much emotional nourishment for love they could get from the 18th-century British novelist Henry Fielding or the 19th-century Russian writer Chernyshevsky, yet it is obvious what really impacted their personal relationship was the Party they both served.

Please tell me what you think about doing for work in the future. And if you are determined to go, I will go with you, okay? (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on August 8, 1957).

Last Sunday, I went to Zhongshan Park with Wang Kun, Lan Xiaohong and Zhang Jingming and had a great time. According to Wang Kun, the department does not allow people to discuss about where everyone is going; need to wait until the rectification movement is over. I think it’s okay, let’s talk about it when you come back. Anyway, you have already registered with the organization. Since the department said to wait, then you should rest easy. (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on August 15, 1957).

Here it is likely to refer to people who were suspected of being “pro-rightist”, faced the problem of “whether they can stay” at work.

My dear, I miss you very much, and it is a pleasant feeling. I often think that you must have changed a lot when you come back, maybe you will not like my intellectual way anymore. But it doesn’t matter; I will learn from you, to be ambitious, energetic, consciously transforming oneself, and truly establishing a revolutionary outlook on life. (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on February 10, 1958).

I hope you work hard, anneal yourself well, and never be complacent. Also, I think that you never talk about your own ideological problems in your letters, which is why I am always worried about this aspect. (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on June 6, 1958).

You said that you don’t think about anything besides working earnestly. What I want to remind you is that you should not restrain yourself in work because of past mistakes. Instead, you should still think and act boldly, and free your mind. If you make mistakes, you should have the courage to correct them. (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on July 7, 1958).

I am always thinking about you, if you work hard and stay in good health, I will be relieved. I don’t know why I’m always so fearful because of you. You are really a big burden to me that I want to get rid of but can’t?! (Letter from Jiang Zongcao to Bao Tong on July 17, 1958).

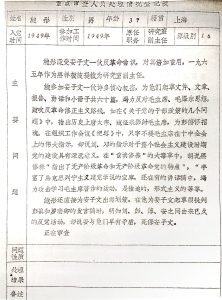

Jiang Zongcao wrote in a “self-reporting” to the Party in 1969:

Lover (translator’s note: meaning husband): Bao Tong, born on October 8th of the lunar calendar in 1932. Before liberation, he graduated from Shanghai Nanyang Model Secondary School (author’s note: it is an error here; should be Nanyang Secondary School). After liberation, for the past 20 years, he has worked in the CCP Organization Department of the East China Bureau and then the Organization Department of the Central Committee of the CCP. Before the Cultural Revolution, he was the deputy director of the Research Office of the former Central Organization Department. He is now under scrutiny and no conclusion has been made yet.

The following is a section that was crossed out in the original text:

During the Cultural Revolution, according to the exposure by the revolutionary masses of the Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee, he was a black minion of the big traitor An Ziwen, and An’s the third-generation successor. Before the Cultural Revolution, until August 1966, that is, until An Ziwen’s cover was revealed, due to my low awareness of the struggle between the two political lines, I had not noticed his problem at all. After he was exposed, I begin to be vigilant in my thinking, and my understanding of his problem has gradually deepened.

Jiang Zongcao continued to work in the Bureau of Translation and Compilation of the CCP, but no letters or writings between the husband and wife were kept during the Cultural Revolution. More than 30 years later, when Bao Tong was imprisoned for the “June 4th” incident, the wife who had been in a dilemma between choosing the “lover” and the “party” during the Cultural Revolution, chose “lover” this time again without hesitation. The following is an excerpt from “Flying” Diary written by Jiang Zongcao from 1989 to 1997 (in Chinese, “flying” has the same pronunciation as “non-criminal”).

July 7, 1989 — this is the 42nd day since Bao Tong was arrested.

In the past 41 days, my heart is extremely calm, because deep inside I know Bao Tong is innocent; but I am also extremely tense and nervous. Because I also know that the most powerful weapon against innocent people is “groundless fabrication”, and fabricating is the easiest thing in the world… No need for any facts, no need for any basis. This had long been proved by the Fengbo Pavilion episode in the Southern Song Dynasty, and it has developed to an extremely proficient level in the unprecedented “Cultural Revolution”. Unusually rich experience has been accumulated in this aspect.

It is in this extreme calm and extreme tension that I have spent the past 41 days and nights. But I still don’t know the answer to the mystery as why Bao Tong was arrested, or to be more precisely, what allegations are charged against Bao Tong. Now the answer is finally revealed.

According to the report made by the State Council to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, Bao Tong committed two heinous crimes. The first was that he leaked the country’s most important military and political secret, that is martial law would be imposed. The second is that he presided over a secret meeting to conspire. The original report reads: “In the evening of (May) 17, Bao Tong called some members of the Central Political System Reform Office, and after leaking the secret of imminent martial law, he delivered a farewell speech, warning participants not to disclose anything discussed in the meeting. Otherwise, they would a “traitor” like “Judas”.

If the report said that Bao Tong had found a special agent or traitor to “conspire” to do something, Bao Tong wouldn’t be able to clear himself even if he jumped into the Yellow River. But Bao Tong “leaked secrets” to some personnel in the Political Reform Research Office, so the participants had to testify. Of course, Chen Xitong can “represent the State Council” and make something out of nothing, but whether the participants will fabricate with him is not up to Chen Xitong. Secondly, there is no specific content of the “conspiracy and planning” stated, which shows that it is purely false intimidation.

If I could not sleep at night before, then on the night of July 7, 1989, thanks to Chen Xitong’s report to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on behalf of the State Council, I slept soundly.

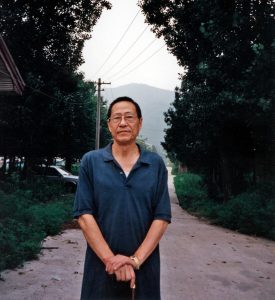

Last Days

After numerous twists and turns of “pandemic precautions”, I finally arrived in Beijing on July 18, 2022. At this time, both father and mother were terminally ill, and they never left the hospital. Mother was dying, and during a month of my visits, the time that she was able to muster her energy and recognize me was about 20 seconds.

In their bedroom, the bed was empty, and bedside cabinets were piled up with medicine boxes. On my mother’s bedside table laid a copy of “900 Sentences in Spanish” and a copy of “The Forests in Norway” opened and folded a few pages. And on my father’s bedside, besides the regular Chinese dictionary “Ci Hai” (Word-Ocean) and English textbooks and English-Chinese dictionary, there were also a dog-eared copy of “Gong Zizhen’s Notes on Poems in the Year of Ji Hai”; a copy of “Shuangzhaolou Poems and Proses” that I brought to him from Hong Kong; as well as a Chinese translation of “The Death of Socrates”. Thinking of the joke they used to say that the two of them would “never read the same book in their lives”, I couldn’t help smiling amidst the sadness.

When I first came to visit my father in the hospital, he could still use the Ipad to read books and surf the Internet, and therefore was not completely cut off from the outside world. When he had energy, he liked to surf the social media “Twitter”. He said, “Twitter is addictive. At a time of revolution, people tend to follow whoever is the most extreme. Twitter is very interesting, the more extreme the speech, the more’likes’.” I tried to persuade him and said, “Don’t waste your energy interacting anonymous abuses”, and he said, ” Interaction online can effectively prevent ‘senile dementia'”. He even asked me to help him open a hidden account, and the two “Twitter” accounts interacted with each other for questions and answers, very lively.” From then on, almost every time I visited him, I would ask him some questions on current affairs that some political analysts asked me to convey to him. But this time it was an exception that basically he had no interest in talking about current affairs. But he made a most substantive comment by saying: “Chinese people today are still living under the shadow of the Cultural Revolution. At that time, only one thing was true, which was ‘whoever opposes Chairman Mao will be gotten rid of’. Yet such a low-level thing is passed on till today. So, what’s point of making any comment?!”

Gradually our conversation boiled down to some of life’s ultimate questions. He talked about Christianity many times and had some real understanding. He said, “Truth, kindness, and beauty are actually the same thing! It’s very profound!” He asked me to find out where this idea first came from, and I believe he had never read anything about medieval theological works such as St. Thomas Aquinas. What he talked about most was Confucius, Mencius, and Zhuangzi, whom he referred to as the model of human behavior. I then asked him what the relationship between Confucius, Mencius, Zhuangzi and the Communist Party was in his life. He said, “When I’m in the Party, I help it with my words and deeds sincerely; when I’m outside of the Party, I criticize it with my words and deeds sincerely too. This is the principle of how to be a real man according to Confucius, Mencius, and Zhuangzi.” I remember once he said that in essence, the teaching of Confucius, Mencius, and Zhuangzi is “the same as humanism and they are all about realization of human value.”

The last book my father finished reading was “On the Boundary Between Heaven and Man” by Yu Yingshi. After that, he no longer had the strength to lift the Ipad that had accompanied him for nine years. And his comment after reading the book was that “China is no longer the same China after the Mao Zedong era”.

In the early morning of November 9, 2022, he was struggling with vomiting, and his thoughts continued. In a series of unintelligible words, the only phrase that I could clearly discern was “… unfounded worries…”. Although those were the last words he left in the world, I will never know its exact meaning.

This article first appeared in Yibao China on 11/14/2022.