By JIANLI YANG

n spring 1989, I returned from my study in America to China to participate in the Tiananmen demonstrations. I was luckier than many protesters, narrowly escaping the June 4 massacre. I escaped to America, and have since continued my human-rights work.

As a longtime student of history and a close observer of politics in China and the U.S., I have poignantly realized that in politics, extremism is the rule rather than the exception—yet almost every civilizational advance throughout history has come when political forces overcame that tendency. One of the characteristics of extremism is seeing people with different opinions as irreconcilable enemies. Extremism in the U.S. now even endangers American democracy itself. The two major political parties have little interest in working together to find common ground on the most hotly contested issues.

Even in China where we, Chinese democrats, command the high moral ground vis-a-vis the CCP dictatorship, it is neither moral nor strategic to treat everyone in our opposite political camp as a mortal enemy. This is the lesson I have learned from the two Tiananmen tank men.

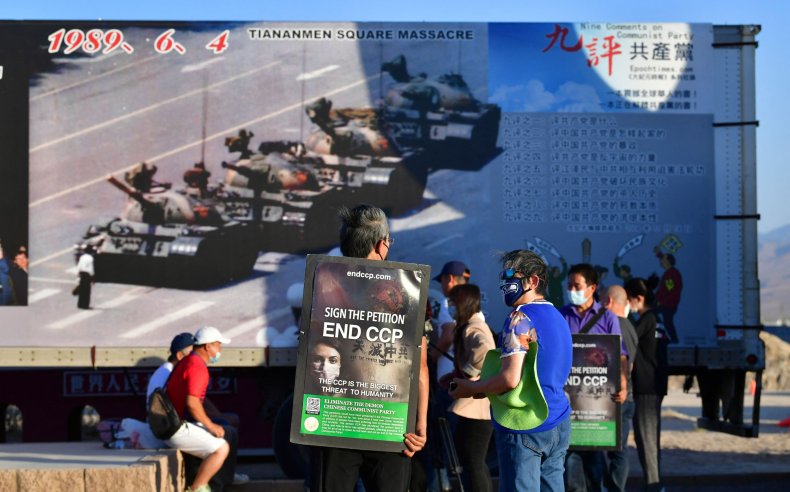

Part of its power was not just that it showed one completely vulnerable man standing in front of an array of tanks, but also that the world knew about the events that had preceded the moment. The Tank Man had survived a massacre, yet here he was, still risking his life.

I was near Tiananmen Square in the early morning on June 4, just as gunfire began. At one point, I was so close to the soldiers that I shouted to them in their trucks and told them not to shoot. We even sang songs that every Chinese knows, trying to touch their hearts. But when they received the order, they just opened fire. I saw many killed, including 11 students who were chased and run over by tanks on that fateful day.

The Tank Man photo was taken the next day, on June 5, the morning after, when the massacre was still ongoing. By any measure, this image is one of heroism. But how many heroes do we see?

Nearly nine years after the picture was taken, the writer Pico Iyer said: “The heroes of the tank picture are two: the unknown figure who risked his life by standing in front of the juggernaut, and the driver who rose to the moral challenge by refusing to mow down his compatriot.”

Not only did the driver refuse to kill, but he undoubtedly disobeyed orders and risked—and perhaps received—punishment in order to save a countryman’s life.

Unfortunately, I failed to see this at the time.

After watching troops kill on June 4, I saw a young soldier standing alone near the Square. He wasn’t wearing a helmet and he didn’t have a gun. He looked like a teenager.

We chased him because we were sad and angry. I punched him. More and more gathered and also beat him. At one point he yelled, “I didn’t do it! I didn’t shoot!”

I realized a tragedy was taking place. But it was too late to stop the violence. I left the scene without looking back. A few minutes later, I knew from the loud shouts behind me that he’d been killed, and I began to cry.

Like the other soldiers, that teenager had been forced to come to Beijing to kill. Like us, he was powerless to stop the tragedy. He had probably refused to shoot, choosing instead to desert. If so, he was a hero, as well—another Tank Man in the opposite camp.

But I was not.

I let anger get the better of me. When I saw this soldier, I saw him only as my enemy. I can’t imagine the pain he suffered and what he was thinking while dying.

For 33 years, I have been mourning him. I think about his family, and I still look to a day when I find them and share my guilt.

In June 1989, Beijing’s streets witnessed many Chinese like Tank Man, standing face-to-face with soldiers who were killing. Yet there were also some soldiers, like the second Tank Man and the deserter, who refused the Communist Party’s orders.

Remembering this, I am convinced that the natural desire for dignity and freedom are not only present among dissidents. They exist in everyone. This is also true of American politics. Because we are in different political camps, especially in a democracy, that does not mean we are sworn enemies. We must not lose sight of the fact that common sense and conscience can prevail in every heart, even under extreme circumstances.

Common ground must be found on the most vital issues facing Americans. Yes, American politics right now is extremely polarized. And now more than ever, the times call on Americans to see the other side as equally human—to be like the two Tiananmen Tank Men, and look to their reserves of courage and compassion to stand up to, and for, the times.

Jianli Yang, a Tiananmen Massacre survivor and a former political prisoner of China, is founder and president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China and the author of For Us, the Living: A Journey to Shine the Light on Truth.

This article first appeared in Newsweek on June 4, 2022.